Magnetism is one of the most intriguing and mysterious forces in the natural world. From the simple fridge magnet that holds your shopping list to the powerful magnetic fields of the Earth that guide migratory birdsmagnets play a vital role in both everyday life and the vast cosmos. But what exactly is magnetism? How do magnets workand why do they attract or repel certain materials? This article will take you on a journey through the physics behind magnetismunraveling its secretsexploring its many manifestationsand revealing how this invisible force shapes the world around us.

The Fascination with Magnets: A Brief Introduction

Magnets have captivated human imagination for thousands of years. Ancient civilizations discovered naturally occurring magnetic rocksknown as lodestoneswhich mysteriously attracted iron. The Chinese were among the first to use magnets for navigationdeveloping compasses that transformed exploration and trade. Over centuriesscientists and philosophers have sought to understand the underlying principles that govern magnetic phenomena.

Todaymagnetism is more than a curiosity—it’s a fundamental force studied deeply by physicsintertwined with electricityand harnessed for countless technologies including electric motorsMRI machinesand data storage devices. The journey to understand magnetism has also paved the way for some of the most profound insights into the nature of matter and energy.

What Is Magnetism? An Intuitive Overview

At its coremagnetism is a force—a special kind of interaction between objects that can cause attraction or repulsion without physical contact. Magnets produce magnetic fieldsinvisible regions of influence that can exert forces on other magnets or magnetic materials. The north and south poles of a magnet define the directions in which these forces act.

Magnets can attract materials like ironcobaltand nickel. Howeverthey do not attract everything; for instancewoodplasticand glass remain unaffected. This selective behavior hints at something deeper going on at the atomic and subatomic levels.

The simplest way to picture a magnet is as an object with two poles—north and south—where magnetic field lines emerge from the north poleloop through spaceand enter the south pole. These field lines are more than conceptual; they represent real forces that act on other magnetic moments within materials.

But what generates these magnetic fields? Why do only certain materials respond? The answers lie in the microscopic world of electrons and their quantum behavior.

The Atomic Roots of Magnetism

Everything in the universe is made of atoms—tiny building blocks composed of a nucleus surrounded by electrons. To understand magnetismwe must zoom in to the scale of electrons.

Electrons have an intrinsic property called “spin,” which can be imagined as a tiny magnetic momentmuch like a tiny bar magnet. Each electron’s spin generates a small magnetic field. Howeverthis analogy only scratches the surfaceas the true quantum nature of spin is more complex and less intuitive.

Besides spinelectrons also orbit the nucleuscreating an additional magnetic moment due to their motion. In many atomsthese magnetic moments cancel out because electrons come in pairs with opposite spinsresulting in no net magnetism. Howeverin some atomsespecially those of ironcobaltand nickelthe magnetic moments do not fully cancel outleaving a net magnetic moment.

When these atomic magnetic moments align in a materialtheir individual tiny fields add upcreating a strongmacroscopic magnetic field that we observe as a magnet. This alignment can be permanent or induced temporarily depending on the material’s structure and conditions.

Types of Magnetism: From Diamagnetism to Ferromagnetism

Magnetic behavior in materials varies widelydepending on how the atomic magnetic moments interact and align. Physicists classify magnetism into several types:

Diamagnetism is a weak form of magnetism present in all materials. When exposed to a magnetic fielddiamagnetic materials generate an opposing magnetic fieldcausing slight repulsion. This effect is very subtle and usually overshadowed by stronger magnetic behaviors.

Paramagnetism occurs in materials with unpaired electrons that do not interact strongly with each other. When placed in a magnetic fieldthese atomic moments align somewhat with the fieldcausing weak attraction. Howeverthis alignment disappears once the external field is removed.

Ferromagnetism is the phenomenon responsible for permanent magnets. In ferromagnetic materials like ironatomic magnetic moments spontaneously align parallel to each othercreating a strongpersistent magnetic field even without an external field. This alignment is stabilized by quantum mechanical interactions known as exchange interactionswhich favor parallel alignment.

Other types include antiferromagnetismwhere adjacent atomic moments align oppositelycancelling each other outand ferrimagnetisma mixed form seen in some complex oxides.

Understanding these types reveals why some materials can be turned into magnetswhile others cannot.

The Quantum Mechanics Behind Magnetism

Delving deeperthe foundation of magnetism lies in the strange and fascinating world of quantum mechanics. Unlike classical physicswhere electrons were imagined as tiny charged spheres orbiting the nucleusquantum mechanics describes electrons as wavefunctions with probabilistic distributions.

The electron’s spin is a purely quantum property with no classical analogue. Spin quantization means electrons can have only certain discrete spin statesusually described as “spin-up” or “spin-down.” The Pauli exclusion principlewhich states that no two electrons in an atom can have identical quantum statesforces electrons into specific arrangements that influence magnetic properties.

The exchange interaction is a purely quantum mechanical effect arising from the indistinguishability of electrons and their spins. This interaction causes electrons in certain materials to prefer aligning their spins parallel or antiparallelleading to ferromagnetism or antiferromagnetism respectively.

Quantum mechanics also explains the limits of magnetism—why it disappears at high temperatures (thermal agitation overcomes magnetic alignment) or why only specific elements exhibit strong magnetic properties.

Magnetic Domains: How Magnets Maintain Their Strength

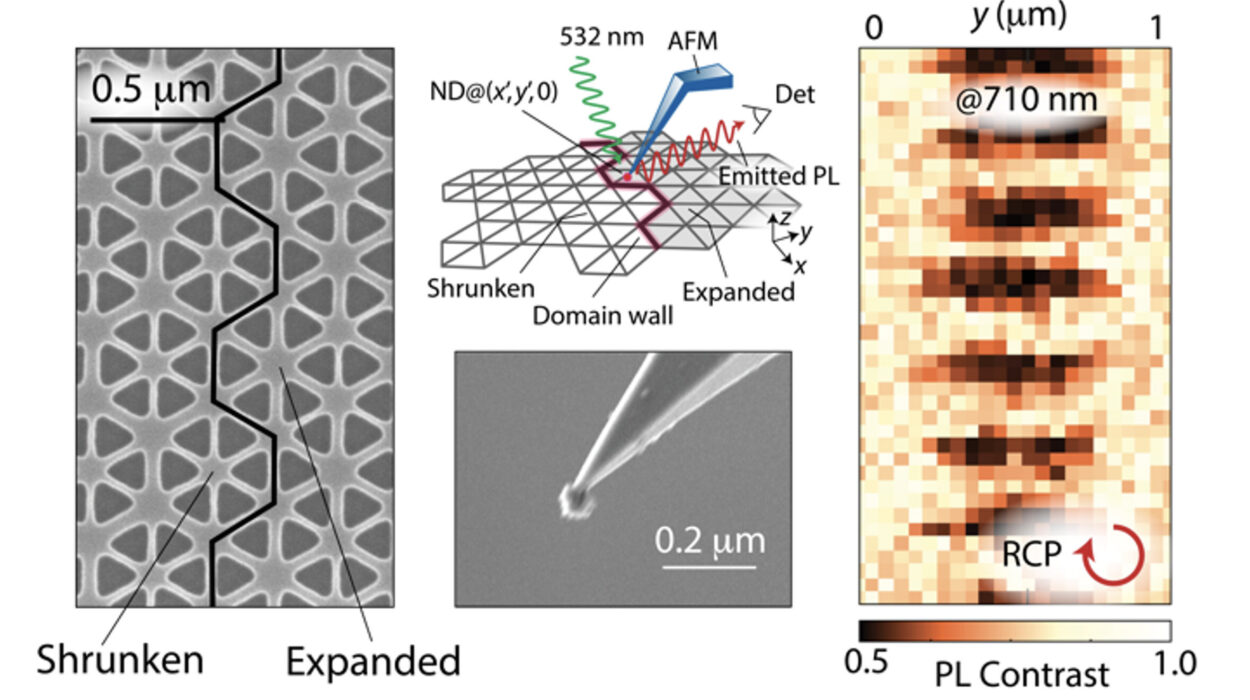

Even in ferromagnetic materialsmagnetic moments are not uniformly aligned throughout the entire piece of metal. Insteadthese materials break down into regions called magnetic domainswhere moments are aligned internally but point in different directions between domains.

Domains reduce the overall magnetic energy of the system by minimizing stray magnetic fields. When a ferromagnetic material is magnetizedthese domains grow or shrinkaligning more moments in the same direction and creating a strong overall magnetic field.

The boundaries between domainscalled domain wallsplay a crucial role in magnetization and demagnetization processes. Applying external magnetic fields can shift domain wallsenhancing or weakening magnetism. This behavior is fundamental to how magnets are made and how they function in devices.

How Magnets Interact: Attraction and Repulsion

The defining characteristic of magnets is their ability to exert forces on each other. Opposite poles attractwhile like poles repel—a fact familiar from childhood experiments. But why does this happen?

Magnetic fields are generated by moving electric charges and intrinsic spinand these fields interact with other magnetic moments. When two magnets approachtheir fields interact—if their field lines complement each other (north to south)the magnets pull togetherminimizing energy. If the fields oppose (north to north or south to south)they push apart to avoid high energy states.

This principle of field interaction governs not just bar magnets but also electromagnets and the magnetic forces within materials.

Electromagnetism: The Unity of Electricity and Magnetism

Magnetism is intimately connected with electricity. This connection was revealed in the 19th century by Hans Christian Ørstedwho discovered that an electric current produces a magnetic field. This breakthrough led to James Clerk Maxwell’s formulation of Maxwell’s equationswhich unify electricity and magnetism into a single framework—electromagnetism.

Electric currents generate magnetic fieldsand changing magnetic fields induce electric currents—a phenomenon known as electromagnetic induction. This principle is the basis for transformerselectric generatorsand countless electronic devices.

Electromagnetswhich use electric current to create magnetic fieldscan be switched on and offand their strength can be controlled. They are fundamental to modern technologyfrom MRI machines that peer inside our bodies to maglev trains that float above tracks.

Magnetic Materials and Their Applications

Magnets and magnetic materials are everywhere. From simple refrigerator magnets to sophisticated hard drivesmagnetism underpins modern life. Magnetic materials are chosen based on their properties for various applications.

Permanent magnetstypically made from ferromagnetic alloys like neodymium-iron-boronmaintain a stable magnetic field and are used in motorssensorsand loudspeakers.

Soft magnetic materialssuch as silicon steelhave low coercivity and can be magnetized and demagnetized easily. They are used in transformer cores and electromagnets.

Magnetic storage devices use tiny magnetic domains to encode dataallowing computers to save vast amounts of information.

In medicinemagnetic fields are used in MRI technology to produce detailed images of soft tissuesrevolutionizing diagnostics.

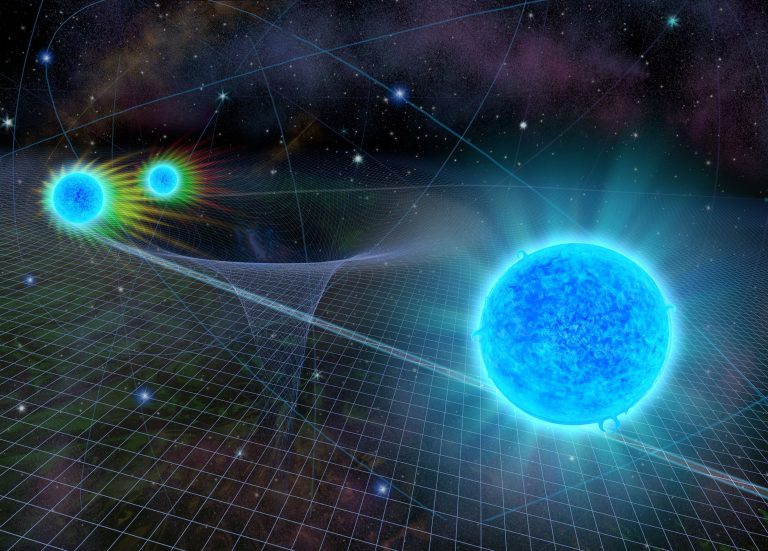

The Earth’s Magnetism and Its Importance

Our planet itself is a giant magnet. The Earth’s magnetic field is generated by the movement of molten iron in its outer corecreating a geodynamo effect. This field extends far into spaceforming the magnetospherewhich shields life on Earth from harmful solar radiation.

The magnetic poles wander over time and even flip entirely in geological cyclesleaving clues in rock formations that help scientists understand Earth’s history.

The magnetic field also aids navigationboth for humans using compasses and for animals like migratory birdsturtlesand whales that rely on geomagnetic cues to find their way across vast distances.

Recent Advances and the Future of Magnetism

Research into magnetism continues to push boundaries. New materials such as spintronic devices exploit electron spin rather than chargepromising faster and more efficient electronics. Magnetic monopoleshypothetical particles with a single magnetic poleremain a fascinating theoretical pursuit.

Scientists are also exploring ways to manipulate magnetism at the nanoscaleleading to advances in data storagequantum computingand medical therapies.

Conclusion: The Invisible Force That Shapes Our World

Magnetismonce a mysterious forceis now understood through the lens of atomic physics and quantum mechanics. Yet its invisible reach continues to influence technologynatureand our daily lives in profound ways.

From the spin of tiny electrons to the protective shield around our planetmagnetism reveals the elegance and complexity of the universe. By exploring how magnets workwe gain not only scientific knowledge but also a deeper appreciation for the unseen forces that connect and sustain the world around us.