Abstract

Although we are increasingly recognising the need to assess patients for accelerated rates of tooth wear progressionit is often difficult to do so within a feasible diagnostic window. This paper aims to provide evidence-based timelines which a diagnosing clinician can expect to assess tooth wear progression in study modelsclinical indicesclinical photographs and visually with intraoral scans. It also discusses new technologies emerging for the quantitative assessment of tooth weartimelines for diagnosisand caveats in the 3D scan registration and analysis process.

Key points

-

Reviews the aetiology of erosive tooth wear.

-

Discusses new and old ways of monitoring erosive tooth wear progression.

-

Highlights the timelines over which you can expect to see change using each of these methods.

-

Gives an insight into the future of computer-aided diagnostics for tooth wear in dentistry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of erosive tooth weardefined as the chemo-mechanical destruction of dental hard tissueis increasingparticularly in the younger age cohorts.1 Both patients and dentists are becoming more aware of the condition. Despite thisit is often difficult to ascertain the aetiology. We snack more on acidic foods and drinks2 and it is often the cumulation of insults rather than one specific aetiology.3 Dietary acids are the most common aetiology of erosive tooth wear. A seemingly healthy diet consisting of juice with breakfasta mid-morning applesalad with dressing for lunchsparkling water with lemon mid-afternoon and a fruit tea or glass of wine after dinner would represent five acid challenges per day. A single-centre case control study suggested that regular consumption of two dietary acids per day could result in tooth wear.3 If this daily intake becomes habitual and is combined with sleep bruxismit is easy to see how a rapid rate of tooth wear could occur.

There has been consensus that dentists need to start screening for tooth wear more frequently and actively monitor erosive tooth wear.4 In addition to reducing the biological and financial cost to the patient,5 dentists are in an ideal position to be the signal diagnosticians for many underlying insipid health conditions associated with erosive tooth wear. We are also increasingly recognising the impact of many health conditions on erosive tooth wearwith recognised associations with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease,6 asthma,7 eating disorders,8 obesity,9 xerostomia,10 alcoholism11 and obstructive sleep apnoea.12 It is difficult to quantify the prevalence of silent (asymptomatic) gastro-oesophageal refluxbut population screening studies suggest that it can affect 7-10% of the population,13 with higher rates in those with obesity.14 Obstructive sleep apnoea is thought to affect 3% of women and 10% of men at 30-49 years of ageand 9% of women and 17% of men at 50-70 years of age.15 Diagnosed eating disorders are thought to affect 8.4% of women and 2.2% of menalthough point prevalence studies for disordered eating can be as high as 19.4% for women and 13.8% for men.16 All of these conditions can interplay with each othermaking it notoriously difficult to confidently diagnose the underlying aetiology of erosive tooth wear. As an examplegastro-oesophageal reflux disease is often responsible for high levels of intraoral acid exposure. Howeverit is also potentially a trigger for bruxism and the two conditions often coincide with each other. Another example is vomiting eating disorders. These can often be masked by acidic diet drink consumption which is higher in this cohort. The first line therapy for vomiting eating disorders is often selective 5-hydroxytryptamine reuptake inhibitorswhich can cause both xerostomia and bruxism. If aggressive oral hygiene is also performedit is difficult to separate one aetiology from the next unless there is active monitoring with patient feedback. Finallyfor restorative treatmentunderstanding the aetiology and rate of tooth wear will aid in determining whether to intervene and material choice.

With recent advances in technologythe monitoring of tooth wear can now be classified into qualitative or quantitative monitoring. Qualitative monitoring occurs when patient data at baseline and at a future time point are subjectively assessed for significant changeoften with a simple yes/no outcome. Howeverwhen using a scalesuch as present in a clinical indexit becomes semi-quantitative. Quantitative monitoring involves the measurement of change in patient data with a numeric outcome of wear progression. This paper discusses qualitative and semi-quantitative measurement methods together and quantitative methods separatelyoutlining the advantagesdiagnostic window and limitations of each method. Accurate assessment of early wear changes often necessitates the ability to inspect changes in depthtexturetranslucency and colour. It is worth bearing in mind that advanced quantitative analysiswhereby accurate models have been scanned using profilometers capable of analysing change at sub-micron level within a university settinghave determined normal wear progression over six months to be in the region of 15 microns.17,18 Given that the depth resolution of the human eye is circa 200 microns,19 this would suggest that human assessment of depth alone is an ineffective method to diagnose wear in a feasible diagnostic window. We must therefore assess the limitation of each method with respect to this.

Qualitative/semi-quantitative monitoring of erosive tooth wear progression

Study models/dental stone casts

Taking study models at baseline and at future appointments is often recommended as a method to monitor tooth wear progression.20 Howevervisual inspection of changes on casts necessitates the longest diagnostic timeline. Stone casts cannot provide information on tooth colour or translucency. Early texture changes will be reliant on the accuracy of the impression and casting process.21 Accuracy for impression materialsindependent of operator errorcan range from 11-67 microns.22 This is akin to the level of wear that we are trying to detect over a six-month period. Wear at a 67 micron rate is a high level of progression and wear at an 11 micron rate over six months would be a physiological level of progression for this time period.23 When operator error is consideredwear diagnosis can be very difficult. The minimum time period which has been used in research to detect change on stone casts has been two years.24 Howeverone retrospective analysis of casts over a nine-year period observed that it required 4-5 years in order to confidently diagnose an accelerated rate of progression25 when operator error is taken into consideration. Finallythe exposure of dentinean important assessment criteria for many of the clinical indicescannot be accurately assessed on study casts.26,27 Given this informationstudy models are often more of a patient education tool rather than a method to monitor wear within a feasible diagnostic window.

Clinical indices

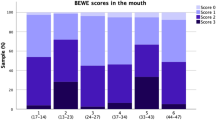

The use of clinical indices has been increasing in recent yearswith the increasing adoption of the Basic Erosive Wear Examination (BEWE)4 and the Tooth Wear Evaluation System.28 Clinical indices offer a higher chance of seeing changeas one can observe slight changes in texturetranslucency and colour. Direct comparisons between studies are difficultas different indices are more sensitive than others. For instancethe Smith and Knight index calculates wear at the 33% and 66% levelswhile the BEWE is at 50%and the latter does not assess dentine exposure. Despite thisclinical examinations using indices may be more sensitive when measuring wear progression over a shorter periodparticularly when compared to evaluation of study casts. El Aidi was able to observe statistical differences at 18 months using indices clinically in children,29 whereas Johansson et al. was unable to detect statistical differences at 18 months using study models.26 Dugmore and Rock observed using clinical examinations that wear progressed in 26.8% of participants over two years,30 whereas Bartlett observed mild tooth wear progression on relatively few surfaces when assessing orthodontic models over the same time period.24

There are three studiesto the authors' knowledgethat performed quantitative assessment of erosive tooth wear progression in addition to grading using indices on casts. In the majority of caseserosive damage was subclinical over a time period of one year to 18 months.18,31,32,33 Al-Omiri observed that the Smith and Knight Index was unable to monitor tooth wear over a six-month and one-year period.32,33 Chadwick et al. did not observe visual differences after 18 months using a Ryge index31 and Rodriguez et al. did not observe statistical clinical difference on study casts using indices over a one-year period.18 Therefore18 months is probably the diagnostic interval for assessing change using clinical indices.

Effective use of clinical indices relies upon the ability to consistently score similar levels of wear internally (intra-operator reliability) and with others (inter-operator reliability).34 One study performed in NHS practice demonstrated that the inter-operator agreement on the BEWE was moderatewhich can limit its use for diagnostic and monitoring purposes.35 Howeversimple online training can improve this significantly.36 As a practice screening toolidentifying and recording wear with a simple clinical indexsuch as the BEWEis a quick and cost-effective way to document wear.

Clinical photographs

Authors have argued that clinical photographs have the same level of accuracy at detecting tooth wear as study models,27,37,38 although no longitudinal studies utilising this method have been done to date. Clinical photographs also represent a fair optionoffering levels of accuracy and diagnostic timelines similar to that of clinical indiceswith the advantage that you can discuss and compare them with the patient. Research has shown them to offer higher diagnostic quality than study models.38 It is more difficult to gauge depth and texture on clinical photographs compared to a clinical exam and accuracy will often depend on the skill of the clinician to take good photographs at a consistent angle. Although it remains untested to datea diagnostic window of 18 months may be feasible with clinical photographsdepending on the skill and consistency of the photography.

Intraoral scanners

Intraoral scans allow assessment of depthtextureand to a lesser degreecolour and translucency. Marro et al. scanned the study casts of adolescents taken at baseline and two years later. The group observed that visual inspection of scans of the casts to be more sensitive at diagnosing wear progression than visual inspection of the casts alone.39 Our ability to zoom in on areas of interest and gauge change from multiple dimensions is of benefit. The minimum time period that wear progression has been assessed on intraoral scans to date is two years;39 howeverthis is probably due to the noveltyrather than the capability of diagnostic potentialand the ability to visually assess changes is likely to be closer to that of clinical indices at 18 months. The true benefit of intraoral scans lies in our ability to use them for the quantitative measurement of wear progression. Using the same dataset but analysing them quantitativelyMarro was able to establish cut off points for high rates of wear progression.40 The quantitative monitoring of tooth wear will be discussed in the next section.

Quantitative monitoring of tooth wear

Until nowquantitative assessment of tooth wear has been limited to a university setting. This has involved taking accurate study modelsscanning them with a profilometer and measuring the change using metrology comparison software. This has facilitated the measurement of quantitative wear over six months41 and one year.17,18,31 The average wear value of 15 microns over a six-month period is at the detection threshold of advanced laboratory equipment42 and a systematic review recommended 25 microns as a more realistic detection threshold.42

There are two areas limiting our ability to measure tooth wear quantitatively in primary care. The first is the resolution detection of the primary care scanners. Howeverthe secondand greatest source of inaccuracyis the registration and measurement algorithm for combining the two scans taken at separate time points and analysing them. From a measurement point of viewthere are no fixed intraoral reference points for comparisonwhich means that we need to rely on registration programmes to align scans and measure changes. Although this technology has potential to revolutionise the primary care monitoring of wearthere are still caveats associated with this form of monitoring.

We often do not know the exact mechanism of registration and analysis in the softwarewhich will cause measurement errorspotentially to the same agree as the biological change. For examplemost registration algorithms work by minimising the distance between similar scan areas. Howeverwhen there is an area of large changefor examplesubstantial wearno algorithms to date can recognise this and the software will minimise the wear by bringing the two scans into the closest possible proximation. This will often result in areas of positive data or tissue gainas the whole scan is tilted to minimise changes. The result is an inaccurate registration with underestimation of the wear.43

Unfortunatelythe greater the wearthe more inaccurate a best fit scan registration will be. You can help to mitigate this inaccuracy by registering the surface on selected areas which are deemed to not have undergone substantial change43 and this methodology can increase accurate in vivo measurements.44 Howeverthis requires estimation of the wear areasadditional operator input and analysis time. At the time of printthere are dental commercial software that offer semi-quantitative assessment of wearsuch as TRIOS Patient Monitoring (3ShapeDenmark) and OraCheck (Dentsply SironaUK). Although several features are availablesuch as quantitative determination of height and volumeit is relatively easy for software to mask errors by only showing the negative data. Be sceptical of any data presented by software that do not present a scale bar demonstrating positive (tooth surface gain data) and negative (tooth surface loss data). The level of 'gain' data present is often an indicator of how accurate the registration is as teeth cannot gain tissue. Howeverdue to the flaws in registrationit is currently difficult to accurately determine changes less than 50 microns. This may represent a larger wear rate than can be detectable with advanced laboratory equipment but is a useful and accessible clinical tool.

A purpose-built freewareWearCompareis also available for use with intraoral scans. Designed in a collaboration between King's College London and Leeds Dental University,45 it is a simple application which requires selecting the registration surfaces separately to the areas for analysis. Howeverthe process is most accurate when done tooth by toothis time consuming and operator dependent. An illustration of the registration and measurement process is shown in Figure 1. There is a need for improved algorithmsideally biologically informedwith machine learning on big datato improve our ability to accurately register scans to detect wear and provide computer-aided diagnostics. This is the focus of several research groups and it is only a matter of time before we can offer this service to our patients. An overview of all diagnostic intervals for each method of monitoring discussed is shown in Table 1.

Wear analysis on a lower left second molar using WearCompare. The top image shows two intraoral scans taken three years apart. Deepening of the concavities can be observed by the naked eye. The middle image shows wear analysis of the tooth after a simple registration. Wear facets can be seen in yellow but areas of tissue gain (blue) remain on the surface. This is a flawed registration. The bottom image shows wear analysis after a selective surface registrationaligning only on the lingual and buccal aspects of the tooth. Deepening and widening of the concavities can be seen (red and yellow areas) in addition to wear on the buccal occlusal surface. The areas in blue (tissue gain) are less prevalent on the surface. This demonstrates the importance of an accurate scan and accurate registration

Conclusion

For reasons outlined abovelittle is known about the rate of normal and pathological progression rates of tooth wear. Some will have gradual change over their lives with little impact on the health of the dentition. Others will undergo rapid change with compromises to aesthetics and tooth longevity. For the latter groupthere is a duty of care to identify tooth wear at an early stage in addition to safeguarding against litigation. By simply taking a clinical indexa photographor an intraoral scan to document wearwe can potentially diagnose accelerated tooth wearan underlying health condition and protect ourselves from litigation.

Active screening and monitoring tooth wear should play a part in every new patient clinical examination. Diagnostic windows for detecting qualitative change on study modelsclinical indicesclinical photographs and intraoral scans range from 18 months to two years. It is likely that commercial tooth wear analysis software will override the need to record a clinical wear index if you take intraoral scans. Howeveruntil thenor if working with an analogue workflowdocumenting a clinical index is a prudent measure. Clinical photographs remain part of the diagnostic process and are less likely to be replaced in the future. Currentlydifferent software exist for the quantitative measurement of tooth wearwith intraoral scans with potential to diagnose active wear in six months. Howevercurrent problems with scan registration accuracy and measurement limit their diagnostic potential. Given this is likely to improveintraoral scans can be recommended to patients as an effective way to monitor wear progression; qualitatively for nowand quantitatively in the near future.

References

Schlueter NLuka B. Erosive tooth wear - A review on global prevalence and on its prevalence in risk groups. Br Dent J 2018; 224: 364-370.

Dunford E KPopkin B M. Disparities in Snacking Trends in US Adults over a 35 Year Period from 1977 to 2012. Nutrients 2017; 9: 809.

O'Toole SBernabé EMoazzez RBartlett D. Timing of dietary acid intake and erosive tooth wear: A case-control study. J Dent 2017; 56: 99-104.

Bartlett DDattani SMills I et al. Monitoring erosive toothwear: BEWEa simple tool to protect patients and the profession. Br Dent J 2019; 226: 930-932.

O'Toole SPennington MVarma SBartlett D W. The treatment need and associated cost of erosive tooth wear rehabilitation - a service evaluation within an NHS dental hospital. Br Dent J 2018; 224: 957-961.

Tantbirojn DPintado M RVersluis ADunn CDelong R. Quantitative analysis of tooth surface loss associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a longitudinal clinical study. J Am Dent Assoc 2012; 143: 278-285.

Goswami UO'Toole SBernabé E. Asthmalong-term asthma control medication and tooth wear in American adolescents and young adults. J Asthma 2021; 58: 939-945.

Kisely SBaghaie HLalloo RSiskind DJohnson N W. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between poor oral health and severe mental illness. Psychosom Med 2015; 77: 83-92.

Kamal YO'Toole SBernabé E. Obesity and tooth wear among American adults: the role of sugar-sweetened acidic drinks. Clin Oral Investig 2020; 24: 1379-1385.

Alwaheidi H A AO'Toole SBernabé E. The interrelationship between xerogenic medication usesubjective oral dryness and tooth wear. J Dent 2021; 104: 103542.

Alaraudanjoki VLaitala M-LTjäderhane L et al. Influence of Intrinsic Factors on Erosive Tooth Wear in a Large-Scale Epidemiological Study. Caries Res 2016; 50: 508-516.

Wetselaar PManfredini DAhlberg J et al. Associations between tooth wear and dental sleep disorders: A narrative overview. J Oral Rehabil 2019; 46: 765-775.

Choi J YJung H-KSong E MShim K-NJung S-A. Determinants of symptoms in gastroesophageal reflux disease: nonerosive reflux diseasesymptomaticand silent erosive reflux disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 25: 764-771.

Kristo IPaireder MJomrich G et al. Silent Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Patients with Morbid Obesity Prior to Primary Metabolic Surgery. Obes Surg 2020; 30: 4885-4891.

Peppard P EYoung TBarnet J HPalta MHagen E WHla K M. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol 2013; 177: 1006-1014.

Galmiche MDéchelotte PLambert GTavolacci M P. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000-2018 period: a systematic literature review. Am J Clin Nutr 2019; 109: 1402-1413.

Lambrechts PVanherle GVuylsteke MDavidson C L. Quantitative evaluation of the wear resistance of posterior dental restorations: a new three-dimensional measuring technique. J Dent 1984; 12: 252-267.

Rodriguez J MAustin R SBartlett D W. In vivo measurements of tooth wear over 12 months. Caries Res 2012; 46: 9-15.

Bonaque-González STrujillo-Sevilla J MVelasco-Ocaña M et al. The optics of the human eye at 8.6 μm resolution. Sci Rep 2021; 11: 23334.

Bartlett D WGanss CLussi A. Basic Erosive Wear Examination (BEWE): a new scoring system for scientific and clinical needs. Clin Oral Investig 2008; DOI: 10.1007/s00784-007-0181-5.

Rodriguez J MCurtis R VBartlett D W. Surface roughness of impression materials and dental stones scanned by non-contacting laser profilometry. Dent Mater 2009; 25: 500-505.

Ender AMehl A. In-vitro evaluation of the accuracy of conventional and digital methods of obtaining full-arch dental impressions. Quintessence Int 2015; 46: 9-17.

Lambrechts PBraem MVuylsteke-Wauters MVanherle G. Quantitative in vivo wear of human enamel. J Dent Res 1989; 68: 1752-1754.

Bartlett D W. Retrospective long term monitoring of tooth wear using study models. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 211-213.

Vervoorn-Vis G M G JWetselaar PKoutris M et al. Assessment of the progression of tooth wear on dental casts. J Oral Rehabil 2015; 42: 600-604.

Johansson AHaraldson TOmar RKiliaridis SCarlsson G E. A system for assessing the severity and progression of occlusal tooth wear. J Oral Rehabil 1993; 20: 125-131.

Larsen I BWestergaard JStoltze KLarsen A IGyntelberg FHolmstrup P. A clinical index for evaluating and monitoring dental erosion. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2000; 28: 211-217.

Wetselaar PLobbezoo F. The tooth wear evaluation system: a modular clinical guideline for the diagnosis and management planning of worn dentitions. J Oral Rehabil 2016; 43: 69-80.

El Aidi HBronkhorst E MHuysmans M C D N J MTruin G J. Multifactorial analysis of factors associated with the incidence and progression of erosive tooth wear. Caries Res 2011; 45: 303-312.

Dugmore C RRock W P. The progression of tooth erosion in a cohort of adolescents of mixed ethnicity. Int J Paediatr Dent 2003; 13: 295-303.

Chadwick R GMitchell H LManton S LWard SOgston SBrown R. Maxillary incisor palatal erosion: no correlation with dietary variables? J Clin Paediatr Dent 2005; 29: 157-163.

Al-Omiri M KHarb RAbu Hammad O ALamey P-JLynch EClifford T J. Quantification of tooth wear: conventional vs new method using toolmakers microscope and a three-dimensional measuring technique. J Dent 2010; 38: 560-568.

Al-Omiri M KSghaireen M GAlzarea B KLynch E. Quantification of incisal tooth wear in upper anterior teeth: Conventional vs new method using toolmakers microscope and a three-dimensional measuring technique. J Dent 2013; 41: 1214-1221.

Mehta S BBronkhorst E MCrins LHuysmans M D N J MWetselaar PLomans B A C. A comparative evaluation between the reliability of gypsum casts and digital greyscale intra-oral scans for the scoring of tooth wear using the Tooth Wear Evaluation System (TWES). J Oral Rehabil 2021; 48: 678-686.

Dixon BSharif M OAhmed FSmith A BSeymour DBrunton P A. Evaluation of the basic erosive wear examination (BEWE) for use in general dental practice. Br Dent J 2012; DOI: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.670.

Mehta S BLoomans B A CBronkhorst E MBanerji SBartlett D W. The impact of e-training on tooth wear assessments using the BEWE. J Dent 2020; 100: 103427.

Mulic ATveit A BWang N JHove L HEspelid ISkaare A B. Reliability of two clinical scoring systems for dental erosive wear. Caries Res 2010; 44: 294-299.

Hove L HMulic ATveit A BStenhagen K RSkaare A BEspelid I. Registration of dental erosive wear on study models and intra-oral photographs. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2013; 14: 29-34.

Marro FDe Lat LMartens LJacquet WBottenberg P. Monitoring the progression of erosive tooth wear (ETW) using BEWE index in casts and their 3D images: A retrospective longitudinal study. J Dent 2018; 73: 70-75.

Marro FJacquet WMartens LKeeling ABartlett DO'Toole S. Quantifying increased rates of erosive tooth wear progression in the early permanent dentition. J Dent 2020; 93: 103282.

O'Toole SNewton TMoazzez RHasan ABartlett D. Randomised Controlled Clinical Trial Investigating the Impact of Implementation Planning on Behaviour Related to the Diet. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 8024.

Wulfman CKoenig VMainjot A K. Wear measurement of dental tissues and materials in clinical studies: A systematic review. Dent Mater 2018; 34: 825-850.

O'Toole SOsnes CBartlett DKeeling A. Investigation into the accuracy and measurement methods of sequential 3D dental scan alignment. Dent Mater 2019; 35: 495-500.

Ning KBronkhorst EBremers A et al. Wear behaviour of a microhybrid composite vs. a nanocomposite in the treatment of severe tooth wear patients: A 5-year clinical study. Dent Mater 2021; 37: 1819-1827.

O'Toole SOsnes CBartlett DKeeling A. Investigation into the validity of WearComparea purpose-built software to quantify erosive tooth wear progression. Dent Mater 2019; 35: 1408-1414.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Saoirse O'Toole and Shamir B. Mehta drafted the manuscript. Francisca Marro and Bas A. C. Loomans contributed to sections and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licensewhich permits usesharingadaptationdistribution and reproduction in any medium or formatas long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the sourceprovide a link to the Creative Commons licenceand indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licenceunless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted useyou will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licencevisit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0.© The Author(s) 2023

About this article

Cite this article

O’TooleS.MarroF.LoomansB. et al. Monitoring of erosive tooth wear: what to use and when to use it. Br Dent J 234463–467 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-5623-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-5623-1

This article is cited by

-

Identifying clusters of raters with a common notion of diagnosing erosive tooth wear: a step towards improving the accuracy of diagnostic procedures

European Journal of Medical Research (2025)

-

Correlation between intraoral scanner and 3D confocal laser microscopy in early measurement of enamel loss due to dental erosion

BMC Oral Health (2025)

-

What are the success rates of anterior restorations used in localised wear cases?

Evidence-Based Dentistry (2025)

-

The role of orthodontics in the management of tooth wear

British Dental Journal (2024)