Abstract

Cocainethe second most used illicit drugis associated with cardiovascularpulmonaryand other complications. Lung involvement associated with cocaine usealso known as "crack lung syndrome" (CLS)can elicit new-onset and exacerbate chronic pulmonary conditions. A 28-year-old female with a history of chronic controlled asthma arrived at the Emergency Department (ED)referring to cocaine inhalationfollowed by symptoms compatible with an asthmatic crisisrequiring immediate steroid and bronchodilator therapy. Radiological studies and bronchoscopy confirmed CLS diagnosis. Despite treatment with oxygenbronchodilatorsand steroidsthe asthmatic crises persisted. Howeverafter 48 hourswe observed a complete regression of the lung infiltrates.

This case highlights the importance of clinical suspicionbronchoscopy findingsand the potential co-occurrence of CLS with asthma exacerbations. While computed tomography (CT) scans can be helpfulthey should not be the only tool to diagnose CLS. The successful management of CLS involves the use of bronchodilatorssteroidsand oxygen therapy and abstaining from cocaine use. Researchers should conduct further studies to diagnose and treat CLS in conjunction with acute asthma symptoms to assist this patient population better.

Keywords: persistent bronchospasmcrack lung syndromecrack lungacute asthma exacerbationcocaine ingestion

Introduction

Cocaine stands as the third most frequently used illicit drug globallytrailing behind cannabis and opioids. According to the 2021 report from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crimethe global prevalence of cocaine in the population aged 15-64 was 0.42%. In the United Statesthe reported prevalence of cocaine use during the 2018-2019 period was 2.14% [1]. Cocaine toxicity is renowned for its association with various complicationsincluding cardiovascular and respiratory issues [2].

The term "crack lung syndrome" (CLS) was coined by Kissner et al. [3] in 1987documenting a case involving a female patient who exhibited pulmonary infiltratesairway obstructionand fever on three separate occasions; these symptoms were promptly resolved following immediate drug interruption. The use of cocaine can cause damage to the lungs due to its effects on the sympathetic nervous system. Cocaine blocks the reuptake of norepinephrine and dopamineleading to an increase in pulmonary arterial pressure and pulmonary vascular toneresulting in lung injurysuch as pulmonary hypertensionthe destruction of the alveolar wallmucous membrane necrosisand impaired macrophage function. These mechanisms contribute to the development of cocaine-induced lung injury (CLS). Clinical presentations related to CLS include alveolar hemorrhagerecurrent pulmonary infiltrates with eosinophiliapneumothoraxpneumomediastinumpulmonary artery hypertrophyand thermal injury to the airway. While chest X-rays provide nonspecific findingscomputed tomography (CT) chest scans may reveal ground glass opacitieshalo signslung alveolar infiltratesand other patterns [3-5].

People who use cocaine are at a higher risk of experiencing asthma exacerbations or similar symptoms. In our case reportwe describe a severe bronchospasm in a patient with asthma who had inhaled cocaine. Despite initial treatment failurethe symptoms were ultimately resolved after 48 hours. We aim to highlight the connection between bronchoconstriction and CLSas demonstrated in our caseand to examine the existing literature on this topic.

Case presentation

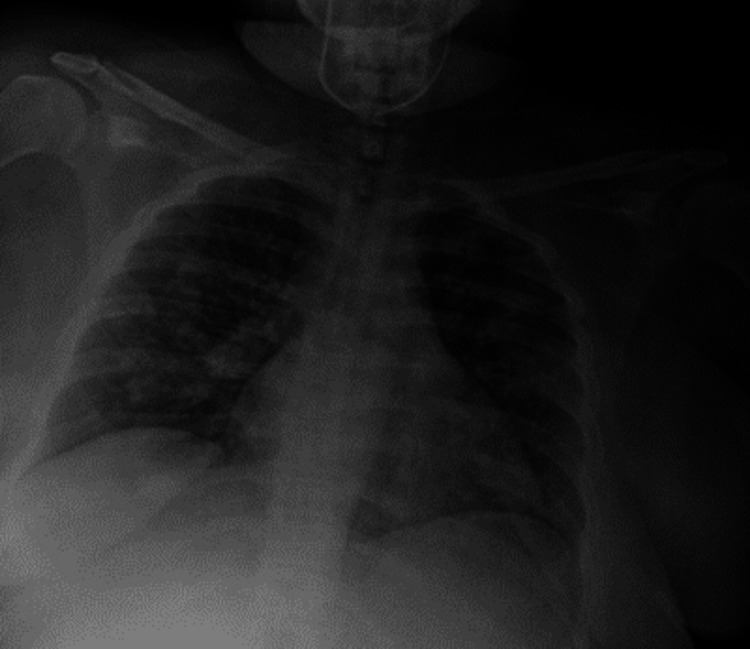

A 28-year-old female with a comprehensive vaccine history for influenza and COVID-19 and a long-standing asthma diagnosis using short-acting beta-2 agonist medication as rescue therapy 3-4 times a monthaveraging one exacerbation per yearand a recent intranasal cocaine use (24 hours before)presented to the Emergency Department (ED). She reported a five-day progressing dyspneachest tightnessconstant holo-cranial stabbing headacheand a persistent nonproductive cough. Initial vital signs were 36.3°Cblood pressure of 110/70heart rate of 132 beats per minute (bpm)and oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 76%. The electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia with no other abnormalitiesand high-sensitivity troponins yielded normal values. Physical examination revealed accessory respiratory muscle use and wheezing. We started asthma exacerbation management with IV 40 mg methylprednisolone once per day and nebulized albuterol/ipratropium for an hour and then every hour. Initial laboratory tests were unremarkable. Influenza and SARS-CoV-2 tests returned negative results. Chest X-rays displayed patchy alveolar infiltratesleading to the initiation of treatment for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) with ceftriaxone and clarithromycin (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Chest X-ray image taken in the anteroposterior projection revealing scattered and diffuse fine reticular lung infiltrates in the periphery.

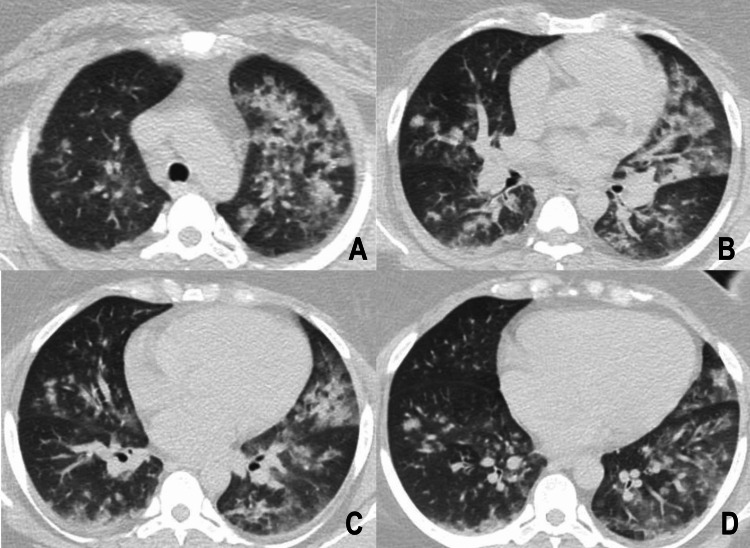

The patient continued to experience persistent coughing and thoracic pain despite initial management. This prompted a high-resolution CT evaluation to investigate other potential causes of lung damageas seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. High-resolution tomography.

(A) Ground glass opacities consolidate in the upper left lobein addition to separate areas with ground glass opacities. (B) Centrilobular nodules with nutrient vessels and areas with a mosaic pattern in the middle lobe. (C and D) Bilateral lower lobes present multiple ground glass centrilobular nodulesand the lower left lobe shows ground glass opacities and a mosaic pattern.

Bronchoscopy testing showed negative results for gramacid-fast bacillimultiple viral agent polymerase chain reaction (PCR)and potassium hydroxide tests. The cytology report showed 963 white blood cellswith 32% lymphocytes47% neutrophils4% eosinophilsand greater than 20% hemosiderin-laden macrophages. Oxygen needs resolved after 48 hoursand bacterial cultures yielded negative results. The patient fully recovered after four days of observation (Figure 3)allowing early hospital discharge. After analyzing this patient's clinicalradiologicaland histopathological featureswe determined that it resembled the CLS.

Figure 3. Chest X-rayanteroposterior projectionshowing the resolution of pulmonary infiltrates.

Discussion

The strengths of this case report rest in its detailed exploration of clinical and radiological findingsproviding valuable insights for emergency and hospital practitioners. The robust discussion highlights the nuanced relationship between asthmatic exacerbations and cocaine use. Howevera notable limitation arises from the absence of histopathological image demonstration because of hospital-patient confidentiality. The lack of pulmonary function tests before and after the reported event hinders a more enriched discussion.

The term "crack lung" describes an acute pulmonary syndrome resulting from the inhalation of crystalline cocaine. Standard CLS features include feverhypoxemiahemoptysisrespiratory failureand diffuse alveolar infiltrates densely populated with eosinophils. Radiological manifestations may include alveolar hemorrhagehypersensitivity pneumonitisand acute respiratory distress syndrome [5]. Kissner et al. introduced this termnoting increased immunoglobulin E levels in a patient with persistent cough and dyspneabecoming relevant in drug-related allergic disease exacerbation [3].

Cocaine induces pulmonary damage through various mechanismsincluding alveolocapillary membrane lesionsincreased alveolar permeabilitydiffuse interstitial damageand the generation of reactive oxygen species. The sympathomimetic effects on pulmonary vasculature lead to pulmonary vasoconstrictionand the repeated increase in pulmonary vascular tone translates into intermittent elevations in pulmonary pressurewhich could lead to pulmonary embolism mimicry and anoxic lung injury. Microvasculature damage increases the release of endothelin-1 (ET-1)translating into vasoconstriction and the vascular leaking of fluid and erythrocytes to the alveolar space; this can be related to CLS presenting with alveolar hemorrhage and pulmonary edema. Cocaine induces severe inflammatory activity with an increase in polymorphonuclear cells and interleukin-8; in chronic usersthis exposure can lead to fibrosismetaplastic epitheliumalveolar wall damageand emphysema. Inhaled products may cause mucosal damage and perforation in the larynx. Macrophage activity against tumors and bacteria decreases because of a diminished capability to generate reactive molecules [4,6].

Bender demonstrated a statistically significant increase in asthma symptoms in drug-using asthmatic patients (5.8% versus 3.7%) [7]. Tashkin et al. evaluated the airway dynamics of cocaine IV users against inhaled drug usersfinding a significant decrease in airway conductance in the inhaled cocaine grouppossibly attributed to airway irritation [8]. There may be exceptional cases where non-asthmatic patients present with an asthma-like CLS clinical presentation with severe obstructive patterns [9,10]. Cocaine has been associated with a threefold increase in the prevalence of new-onset bronchospasm or asthma exacerbationextended hospital staysintubationsand intensive care unit admissions due to asthma exacerbation. Our patient did not experience complications or require mechanical ventilation despite the potential for illicit drugs such as cocaine to trigger asthma crises [11,12].

Rubin and Neugarten published a report on six patients with long-standing asthma who experienced severe exacerbations due to cocaine use; all these patients responded well to standard treatment with bronchodilators and steroids. Howeverour patient had a slower response and showed multiple lung abnormalities on chest X-ray and CT scan [13].

Self et al. [14] conducted a review on the relationship between asthma and drug useincluding cocaine. They mention 18 cases of asthmatic exacerbation with previous cocaine usewhich included the ones reported by Rubin and Neugarten [13] and Kissner et al. [3]and three fatal asthma case series studies found that cocaine use was prevalent in 13% of 39 patients38% of 29 patientsand 44 cases of deaths [14]. Our case survived and had a prompt recovery with an early hospital discharge.

Radiological evaluation is nonspecific. No CT scan finding can confirm a CLS. Cocaine exposure can trigger eosinophilic lung diseasewhich causes ground glass opacitiesnodulesand mosaic patterns. Our patient exhibited diffuse ground glass opacitiescentrilobular nodulesand mosaic patterns [5].

The histopathological characteristics of "crack lung" include alveolar hemorrhagecongestionedemapneumonitisinterstitial fibrosissmall artery medial hypertrophyhemosiderin-laden macrophagesandin rare casescarbon-pigmented macrophages and hemosiderin [15]. Our patient presented with an increase in all types of blood cellsincluding neutrophilslymphocyteseosinophilsand hemosiderin-laden macrophages.

There is no consensus on the best treatment for the acute asthma-like presentation of "crack lung." The previously mentioned cases have reported drug abstinence and standard asthma exacerbation therapy (steroidsbeta-agonistsand oxygen therapy) as their management with no specific difference. Further investigations are necessary to understand this topic.

Conclusions

The patient had a history of cocaine use and was experiencing asthma symptoms that were not responding to standard treatment. Upon conducting a chest CT scanwe found ground glass opacities and centrilobular nodules. Cytology from lung tissue suggested that the patient suffered from CLS. The presence of hemosiderin-laden macrophages further supported this diagnosis.

It is noteworthy that cocaine-induced lung damage can mimic or exacerbate several pulmonary pathologiesincluding asthma exacerbationas exemplified in our case. It is paramount for clinicians to keep a high diagnostic suspicion for CLS when faced with patients with illicit drug use and persistent asthma crises. The lack of high-quality data for diagnosing and treating acute obstructive lung presentations of CLS emphasizes the need for further investigation in this area.

Acknowledgments

Victor A. López-Felix and Luis A. González-Torres contributed equally to the work and should be considered co-first authors.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: Luis A. González-TorresAlan Gamboa-MezaVictor A. López-FélixGabriela Alanís-EstradaJuan Francisco Moreno-Hoyos-Abril

Acquisitionanalysisor interpretation of data: Luis A. González-TorresVictor A. López-FélixGabriela Alanís-EstradaJuan Francisco Moreno-Hoyos-Abril

Drafting of the manuscript: Luis A. González-TorresAlan Gamboa-MezaVictor A. López-FélixJuan Francisco Moreno-Hoyos-Abril

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Luis A. González-TorresVictor A. López-FélixGabriela Alanís-EstradaJuan Francisco Moreno-Hoyos-Abril

Supervision: Luis A. González-TorresVictor A. López-FélixGabriela Alanís-EstradaJuan Francisco Moreno-Hoyos-Abril

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

References

- 1.Trends and correlates of cocaine use among adults in the United States2006-2019. Mustaquim DJones CMCompton WM. Addict Behav. 2021;120:106950. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cocaine intoxication. Zimmerman JL. Crit Care Clin. 2012;28:517–526. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crack lung: pulmonary disease caused by cocaine abuse. Kissner DGLawrence WDSelis JEFlint A. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;136:1250–1252. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.5.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crack lung: an acute pulmonary syndrome with a spectrum of clinical and histopathologic findings. Forrester JMSteele AWWaldron JAParsons PE. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:462–467. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.2.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.High-resolution computed tomographic findings of cocaine-induced pulmonary disease: a state of the art review. de Almeida RRde Souza LSMançano ADet al. Lung. 2014;192:225–233. doi: 10.1007/s00408-013-9553-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Interstitial lung damage due to cocaine abuse: pathogenesispharmacogenomics and therapy. Drent MWijnen PBast A. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19:5607–5611. doi: 10.2174/092986712803988901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Depression symptoms and substance abuse in adolescents with asthma. Bender BG. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99:319–324. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60547-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acute effects of inhaled and i.v. cocaine on airway dynamics. Tashkin DPKleerup ECKoyal SNMarques JAGoldman MD. Chest. 1996;110:904–910. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.4.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Severe obstructive pattern mimicking an asthma exacerbation as first presentation of crack smoking: a case report. Galasso TMazzetta AConio Vet al. Case Rep Intern Med. 2015;2:60–64. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cocaine-induced bronchospasm mimicking acute asthma exacerbation. Zhou CYRicker MPathak V. Clin Med Res. 2019;17:34–36. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2019.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.New-onset bronchospasm or recrudescence of asthma associated with cocaine abuse. Osborn HHTang MBradley KDuncan BR. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4:689–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The effects of cocaine and heroin use on intubation rates and hospital utilization in patients with acute asthma exacerbations. Levine MIliescu MEMargellos-Anast HEstarziau MAnsell DA. Chest. 2005;128:1951–1957. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cocaine-associated asthma. Rubin RBNeugarten J. Am J Med. 1990;88:438–439. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90506-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asthma associated with the use of cocaineheroinand marijuana: a review of the evidence. Self THShah SPMarch KLSands CW. J Asthma. 2017;54:714–722. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2016.1259420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The histopathology of drugs of abuse. Milroy CMParai JL. Histopathology. 2011;59:579–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]