Summary

The development of cancer is an evolutionary process involving the sequential acquisition of genetic alterations that disrupt normal biological processesenabling tumor cells to rapidly proliferate and eventually invade and metastasize to other tissues. We investigated the genomic evolution of prostate cancer through the application of three separate classification methodseach designed to investigate a different aspect of tumor evolution. Integrating the results revealed the existence of two distinct types of prostate cancer that arise from divergent evolutionary trajectoriesdesignated as the Canonical and Alternative evolutionary disease types. We therefore propose the evotype model for prostate cancer evolution wherein Alternative-evotype tumors diverge from those of the Canonical-evotype through the stochastic accumulation of genetic alterations associated with disruptions to androgen receptor DNA binding. Our model unifies many previous molecular observationsproviding a powerful new framework to investigate prostate cancer disease progression.

Keywords: prostate cancercancer evolutionevotype modelevotypesAR bindingordering

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Analysis of genomic data from localized prostate cancer reveals divergent evolution

-

•

The shift away from the canonical trajectory is characterized by AR dysregulation

-

•

Tumors can be classified into evotypes according to evolutionary trajectory

-

•

The evotype model unifies many previous molecular observations

Woodcock et al. show that individual evolutionary trajectories in prostate cancer can be classified into two broad categoriestermed evotypes. This motivates a model of prostate cancer evolution in which Alternative-evotype tumors diverge from those of the Canonical-evotype due to acquired genetic alterations that alter the androgen receptor cistrome.

Introduction

Tumor evolution is a dynamic process1 involving the accumulation of genetic alterations that disrupt normal cellular processesleading to pathological phenotypes.2 While some cancers can be categorized into subtypesoften utilizing pronounced genomic or transcriptomic differencesthe evolutionary processes that give rise to this variation are complex and not well understood.3 Howeverit has been shown that the order of events in some hematological malignancies can be related to prognosis and treatment susceptibility.4,5,6,7

In prostate cancersubtyping schemes have been proposed based on the presence of specific molecular alterations,8 combinations of alterations,9 or gene expression profiles.10 Howeverdetailed investigations by ourselves11 and others12,13 have shown substantial heterogeneity between tumors that presents challenges for simple or consistent subtype assignments.14 Studies investigating evolutionary differences between prostate cancer disease types by categorizing molecular events as “early” or “late” have been shown to be informative in early-onset15 and aggressive disease,16 and the temporal order of genetic alterations has also been shown to be related to the ETS subtype.11 Howeverthe evolutionary factors that drive the emergence of prostate cancer subtypes remains largely unexplored.

To investigate how evolutionary behavior manifests in the variation observed in prostate cancer genomeswe performed three separate analyseseach of which probes different aspects of tumor evolution. In each analysiswe classified the tumors in an unsupervised fashion and subsequently identified sets of tumors that shared the same classes across the analyses. Through this approachwe can identify tumors that display consistent evolutionary properties and use this information to identify likely mechanisms driving prostate cancer evolution.

Results

Data collection and pre-processing

We compiled a dataset from 159 patients with intermediate or low-risk prostate adenocarcinoma sampled after radical prostatectomywho were otherwise treatment naive (87 published previously11). These were whole-genome sequenced (target depth: 50×) along with matched blood controls (target depth: 40×)and 123 summary measurements were generated (STAR Methods; Figure S1).

We adapted an unsupervised neural network with a single hidden layer to perform feature learning on this datasetidentifying associations between inputs to obtain a reduced-dimension set of 30 features (STAR Methods). Using the trained neural networkwe can recast the data for each sample in terms of these features into a form known as the feature representation. Reconstructing the original inputs from the feature representation gave a reconstruction error of 12%indicating that these featuresand the inputs to which they correspondcontain a substantial proportion of the information in the original data. Our approach is a white-box methodmeaning we can identify which inputs contribute to each featureand so we labeled each feature with a brief descriptor of the associated genomic aberrations (Figure S2). We can perform analysis on the feature representation itself while allowing comparison with the results of other analyses using a selection of the original inputs that correspond to the features (STAR Methods).

Classifying tumors by patterns of co-occurring genomic features

Despite the reduced dimensionality of the feature representationapplication of standard clustering methods remains problematic due to the high dimension of features (30) relative to the sample size (159). To mitigate thiswe adopted a two-stage clustering method utilizing a discrimination score we calculated for each feature that quantified the value of each feature in predicting disease relapse (STAR Methods). In the first stagewe applied k-medoid clustering to the feature representation of those features with a high discrimination score (STAR Methods). In the second stagewe performed hierarchical clustering on the cluster centers (medoids) returned in the first stage. The results are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Co-occurrence of genetic alterations distinguishes three metaclusters

After performing feature extractionwe calculated a discrimination score quantifying the relevance of each feature in predicting relapse (green heatmap). Fourteen features (red) were used as inputs for k-medoid clustering with 11 clusters. The medoids of each cluster were used as inputs to hierarchical clustering using all featureswhich revealed three main metaclustersMC-AMC-B1and MC-B2with different profiles as indicated by the dendrogram. The main heatmap shows the medoid feature values for the patients in each clusterordered by the hierarchical clustering (scale to right). The number of samples in each cluster is given below the corresponding cluster medoid. Metacluster colors are denoted by the text above the dendrogram.

We identified two distinct metaclusters that were characterized by different sets of aberrations. Metacluster A (MC-A) showed a high probability of features corresponding to intra-chromosomal structural variants (SVs)SPOP mutationschromothripsisand loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in regions 5q15–5q23.1 (spanning CHD1) and 6q14.1–6q22.32 (MAP3K7ZNF292). MC-B showed more frequent ETS fusionsas well as LOHaffecting 17p (TP53) and regions 19p13.3–13.2 and 22q11.21–22q11.22. The dendrogram indicated additional differences within MC-Band so we further divided it into subclasses MC-B1 and MC-B2with MC-B2 displaying near-ubiquitous TP53 LOH and exhibiting higher probability of ETS fusionsinter-chromosomal chained SVs (cSVs)and LOH at 10q23.1–10q25.1 (PTEN) and 5q11.1–5q14.1 (IL6STPDE4D).

Classifying tumors by mechanism of DNA double-strand breaks

We investigated the influence of androgen receptor (AR) on the DNA breakpoints in these samples. AR is known to precipitate DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) in conjunction with topoisomerase II-beta,17 and AR-associated breakpoints are frequent in early-onset prostate cancer.15,18 Furthermoreit has also been shown that AR-binding behavior can be altered by CHD1 deletion.19 We used a permutation test (STAR Methods) to classify tumors based on whether breakpoints occurred significantly more (labeled as Enriched) or less (Depleted) often proximal to AR-binding sites (ARBSs) than expected if they were independent of AR or Indeterminate tumors that displayed no statistically significant association (Figure 2A).

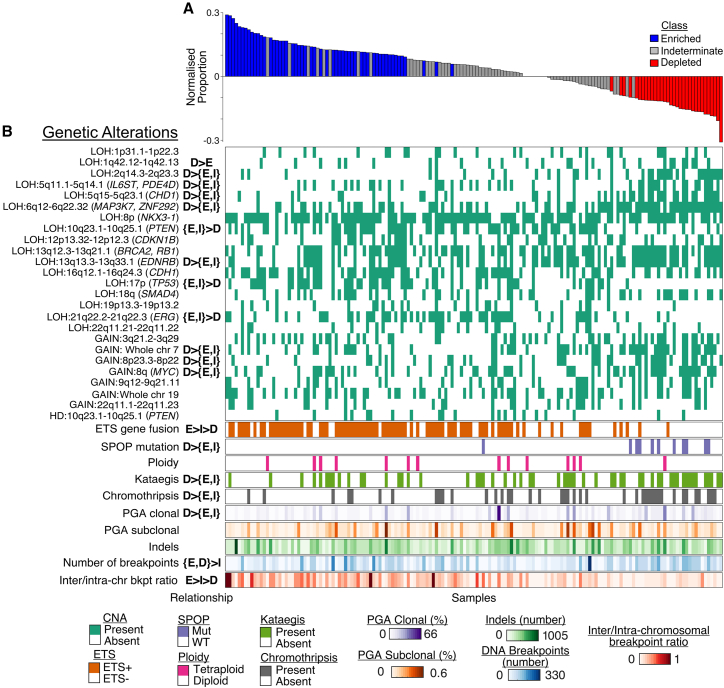

Figure 2.

Classification by proximity of DNA breakpoints to ARBSs reveals common genetic alterations

(A) The proportion of DNA breakpoints within 20 kilobases (kb) of an ARBS for each patientnormalized by the number of proximal breakpoints expected by chance (vertical axis). Tumor samples are ordered according to this normalized proportion (horizontal axis). Classes were determined based on whether the tumor displayed more (Enriched) or fewer (Depleted) proximal breakpoints than expected or there was no statistical significance (Indeterminate).

(B) Heatmaps of genomic features for each patientordered as above. Statistically significant relationships for the three classes are shown in the relationship columnwhere EDand I indicate the EnrichedDepletedand Indeterminate classesrespectively. Braces indicate no relationship between the enclosed classes but that they both display significant differences to the remaining class. Relationships are ordered so the leftmost class(es) are those showing a significantly greater proportion of the corresponding genetic alteration. For Bernoulli variablessignificance was determined with chi-squared test followed by a Fisher’s exact test for each pairwise relationship; for continuous variablesa Kruskal-Wallace test with Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) was used (false discovery rate [FDR]-adjusted p < 0.05 for all tests).

Investigating the ARBS groups in conjunction with the genetic alterations associated with the features (Figure 2B)we found that Depleted tumors had the highest percentage genome altered (PGA) and the highest frequency of multiple copy-number alterations (CNAs)chromothripsiskataegisand SPOP mutations (relationship columnFigure 2B). Enriched and Indeterminate tumors displayed no significant differences for any CNAsbut both showed higher frequencies of CNAs covering PTEN and TP53 than the Depleted group (relationship columnFigure 2B). In the case of ETS fusions and inter-/intra-chromosomal cSV ratiothe Enriched group showed greater amounts than the Intermediate groupwhich in turn showed greater enrichment than the Depleted group. Both Enriched and Depleted tumors displayed higher numbers of breakpoints than Indeterminate tumors. We identified these ARBS groups in two additional datasets: a set of low-intermediate risk tumors from the Canadian Prostate Cancer Genome Network13 and high-risk tumors from the Melbourne Prostate Cancer Research Group in Australia (unpublished). Clustering these groups by CNA proportions showed that groups classified as Depleted clustered together (Figure S3)confirming the association between these CNAs and ARBS-distal breakpoint prevalence.

Classifying tumors through the evolutionary order of key events

The order in which genetic alterations generally occur in tumor evolutionsubsequently referred to as the “ordering profile,” can be inferred using the estimated proportion of tumor cells that display each genetic alteration in each sample.11 We adapted a Plackett-Luce mixture model20 to create a probabilistic model for the relative order of genomic aberrations given the relative subclonal fractions of SPOP mutations and the key CNAs that were identified in our feature extraction (STAR Methods). As a mixture modelit can be used to extract distinct ordering profiles within the population. Inference with this model was performed with differing numbers of clustersand the results used in Bayesian model selection determined that two ordering profiles were optimal (STAR Methods). We therefore defined two classesOrdering-I and Ordering-IIand each tumor was assigned to one of these classes by their mixture weights (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Samples can be differentiated by order of genetic alterations

Phylogenetic trees from individual tumors were used to estimate two ordering profiles using a Plackett-Luce (P-L) mixture model. Tumors were assigned to Ordering-I (top) or Ordering-II (bottom). Horizontal box and whisker plots (5th/25th/75th/95th percentiles) represent the spread of bootstrap estimates of the negative P-L coefficient () for the ith genetic alteration (x axis). Herethe lower the value of the earlier the genetic alteration is likely to occur. The y axis shows the proportion of samples in the mixture component in which the genetic alteration was observed. Colors of the box and whiskers denote the chromosome on which the aberration occurred. Genetic alterations were annotated if they were identified as an ETS fusionoccurred with a proportion above 0.25or were identified in the earliest 5 events; these have chromosomal regions givenwith notable driver genes in the region given in brackets where applicable. Other genetic alterations were not annotated and are displayed with reduced transparency.

The two profiles displayed notable differences. Tumors corresponding to Ordering-I frequently experienced an early 8p LOH (spanning NKX3.1) and ETS fusions. Less frequent LOH of regions covering the RB1BRCA2CDH1TP53or PTEN gene could also occur. This profile occasionally displayed a very early LOH of 1q42.12–42.3. Tumors of Ordering-II consistently displayed early LOH events covering MAP3K7 and 13q (EDNRBRB1BRCA2). Howeverthe earliest eventsa mutation of the SPOP gene and LOH covering CHD1were less frequent. Ordering-II also displayed more frequent copy-number gains. Both orderings showed late gains of chromosome 19. When comparing the occurrence of aberrations between individuals within each orderingwe found that the relative order of alterations was highly variableindicating that they arise stochastically (Figure S4; STAR Methods).

Integrating analyses reveals disease types distinguished by their evolutionary trajectories

Establishing the concordance of these three classification methods (Figure 4A) revealed a remarkable relationship: MC-A is largely a subset of the Depleted group (22/27)and both are almost entirely subsets of Ordering-II (26/27 and 30/32respectively). Quantifying the strength of the pairwise associations using Cramer’s V statistic gives metaclusters and ARBS groups (V = 0.69)metaclusters and orderings (V = 0.58)and ARBS and orderings (V = 0.62). These values indicate a strong association between cluster assignments in these three groups (STAR Methods). We can therefore infer that there exists a subset of tumors that exhibit all the corresponding properties: an evolutionary trajectory (Ordering-II)a breakpoint mechanism (ARBS:Depleted)and characteristic patterns of aberrations (metacluster:MC-A). We therefore propose the evotype model for prostate cancer evolution (Figure 4B)in which canonical AR DNA binding is disruptedthrough the effect of genetic alterations or other causescoercing tumor evolution along an alternative trajectory that results in a distinct form of the disease. We can therefore classify tumors by which path a tumor is most likely to adhere towhich we refer to as its evotype. To perform this classificationwe adopted a majority-vote approach and defined tumors that were assigned to at least two of MC-ADepletedor Ordering-II as belonging to the Alternative-evotype (n = 34) to distinguish them from Canonical-evotype (n = 125) tumors that evolve via the standard route. Each evotype is characterized by a different propensity for certain aberrations (Figure 4C)but we found that no single aberration was necessary or sufficient for assignment to either evotype. Howeverthere were several pairwise combinations of genetic alterations that did result in fixation to one of the evotypes (Figure S5). There were no statistically significant associations (p = 0.05) between the evotypes and tumor stageGleason gradeor prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels (Figure S6).

Figure 4.

Integrating results reveal multiple evolutionary trajectories converging to two disease types

(A) A comparison of how tumors were classified in each of the three previous methods. Each side of the triangle corresponds to a classification methodwherein each bar in the triangle denotes a group identified by that method. Values at the intersections of each bar show the number of tumors that were consistent with both classes. Values outside the main triangle denote the total number of tumors in that class. Colors are those used in previous figures.

(B) A schematic of the evotype model for prostate cancer evolution.

(C) The prevalence of each genetic aberration in each evotypeas determined using the majority consensus of the three classifiers. Aberrations with significant differences between evotypes are colored by the evotype displaying the highest proportion (FDR-adjusted p < 0.05Fisher’s exact test).

(D) A surface plot showing the probability density of a tumor being assigned to the Canonical-evotype relative to the number of aberrations. Common modes of evolutionary progression follow regions of high density as the number of aberrations increases. Exemplars of such routes are indicated by black dashed lines. These are labeled according to their likely evotypea behavioral descriptorand notable driver genes affected by aberrations that are prevalent in the areas along the path to convergence (Figures S7 and S8).

The lack of consistent genetic alterations indicates that there may be multiple individual routes of progression for each evotype. We investigated these trajectories in more detail by developing a stochastic model of the acquisition of genetic alterations and tracking the probability of assignment to each evotype as the aberrations accumulate (Figure 4D; STAR Methods). Initiallythe probability density is concentrated at 0.78the proportion of Canonical-evotype tumors in our sample set. As the number of aberrations increasesthe density diverges to accumulate at 1 (corresponding to unambiguous assignment to the Canonical-evotype) and 0 (Alternative-evotype). In this modelan individual tumor will follow a trajectory through this probability landscapedependent on the type and order of aberrations. Due to randomness in the occurrence of genetic alterationsthere are an enormous number of possible routesbut investigating patterns of aberrations in areas of high probability density reveals common modes of behavior (Figures S7 and S8). Exemplars for these modes are given by the dashed lines in Figure 4D. Notablywhen an SPOP mutation occurs firstit confers high probability (0.91) of progression to the Alternative-evotype (Alternative:Rapid). Other routes to the Alternative-evotype involve the accumulation of multiple individual LOH events involving genes such as MAP3K7CHD1or EDNRB (Alternative:Incremental) in any order. LOH of IL6ST or gain of region 8p23.3–8p22 strongly influences convergence after a number of aberrations have already accumulated (Alternative:Abrupt). Converselyfixation to the Canonical-evotype is dependent on a few key aberrations. Early TP53 loss or ERG gene fusion promotes almost certain fixation to the Canonical-evotype (Canonical:Rapid). Alternativelyloss of regions covering PTEN or CDH1 can coerce a relatively quick progression toward this evotypebut these are rarely the final convergent event in the trajectory (Canonical:Moderate). Indeedthere are aberrations that are often the last step in convergence to the Canonical-evotypeparticularly LOH of 19p13.3–19p13.2 or 22q11.21–22q11.22 or gains of chromosome 19 or region 22q11.1–22q11.23 (Canonical:Punctuated).

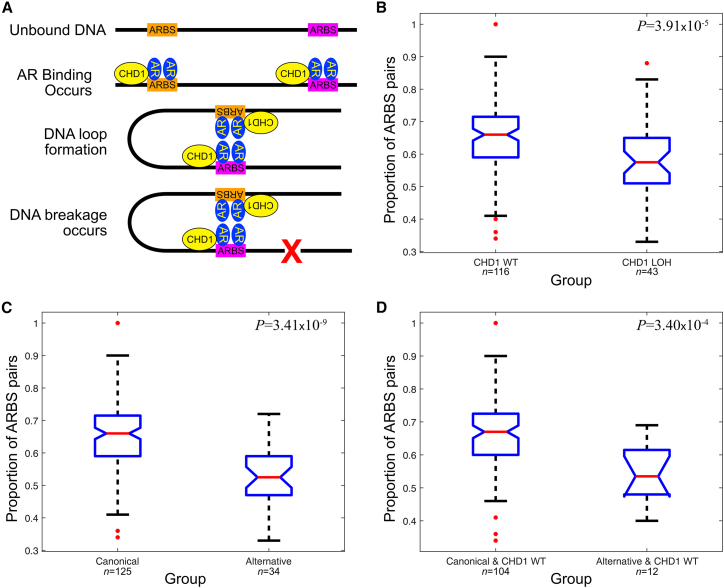

The lack of a single genetic alteration unique to the Alternative-evotype indicates that there may be multiple mechanisms for acquired AR dysregulation that we observe in prostate cancer. We therefore investigated potential mechanisms of AR dysregulation. It has previously been shown that CHD1 protein is involved in AR bindingwhich causes DNA loops that can precipitate DSBs (Figure 5Aadapted from Metzger et al.21). As LOH of the CHD1 locus is significantly associated with the Alternative-evotype (Figure 4C) and is an early event in tumor evolution (Figure 3)we hypothesized that loss of CHD1 in these tumors would be associated with fewer DSBs precipitated through the DNA loop mechanism. We therefore tested whether pairs of adjacent ARBSs required for DNA loops to form by this mechanism are significantly more or less frequently close to DSBsdependent on CHD1 status (STAR Methods). We found that CHD1 wild-type (WT) tumors more frequently displayed DSBs close to pairs of ARBSs than tumors that displayed a CHD1-associated LOH (Figure 5B; p = 3.91 × 10−5). Extrapolating our hypothesis to the evotypeswe found a significant difference between Canonical- and Alternative-evotype tumors (Figure 5C; p = 3.41 × 10−9). This relationship also holds in CHD1 WT tumors of both evotypes (Figure 5D; p = 3.40 × 10−4). These results indicate that CHD1 LOH can drive AR dysregulation in prostate cancer but that other mechanisms also exist in Alternative-evotype tumors.

Figure 5.

Frequency of AR-induced DNA loops associated with DSBs is associated with CHD1 loss and evotype status

(A) A simplified schematic of AR binding to ARBSswhere CHD1 protein is part of a complex that induces DNA loop formation and subsequent DSBsdenoted by the red X.

(B) A notched box and whisker plot shows that adjacent proximal ARBS pairs that are required for DNA loops to form were observed less frequently in the vicinity of breakpoints in CHD1-deficient tumors than CHD1 wild-type tumors.

(C) DSB-associated ARBS pairs occurred less frequently in tumors of the Alternative-evotype than the Canonical-evotype.

(D) DSB-associated ARBS pairs occurred less frequently in CHD1 wild-type tumors of the Alternative-evotype than the Canonical-evotype. All p values were determined through a one-sided Mann-Whitney U test.

Discussion

Taken togetherour findings reveal prostate cancer disease types that arise as a result of divergent trajectories of a stochastic evolutionary process in which specific genetic alterations can tip the balance toward convergence to either route. Unlike the evolution of specieswhich involves ongoing adaptation to a perpetually changing environmenttumor evolution has a definable endpoint—a disease state that leads to the death of the host. It follows that the more “evolved” tumors are closer to this endpointwhich has obvious implications for risk stratification. We therefore proposed that our evolutionary model implied two factors associated with riskthe evotype itself and the degree of progression relative to that evotype. We investigated this principle using follow-up information based on time to biochemical recurrence (serum PSA > 0.2 ng/mL for two consecutive measurements) after prostatectomy.

Initiallywe found that classifying by evotype alone provides a significant association with time to biochemical recurrence (Figure 6A; p = 0.0256)displaying a higher hazard ratio (HR = 2.30) than stratification by well-known genetic alterations such as PTEN loss (HR = 1.42p = 0.336; Figure S9A)TP53 loss (HR = 2.03p = 0.0497; Figure S9B)or ETS status (HR = 1.64p = 0.179; Figure S9C). Howeverit performed worse than other metrics known to be associated with outcomesuch as tumor mutational burden (TMB)which led to HR = 4.50 and p = 0.000110 (Figure 6B)or histopathological grading via the ISUP Gleason grade scorewhich gave HR = 4.69 and p = 0.0000629 (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Utility of evotype model in survival analysis

Kaplan-Meier plots for (A) the evotypes; (B) 20 tumors with greatest tumor mutational burden (high-TMB) against the remainder (low-TMB); (C) ISUP Gleason grade; (D) 10 tumors with highest TMB for each evotype (high-TMB Alternative and high-TMB Canonical) against the remainder (low-TMB combined); (E) the ISUP Gleason grade ≥3 tumors in the high-TMB evotype classes (Evo-TMB-Gleason high) and the remainder (Evo-TMB-Gleason low); (F) Alternative-evotype tumors in MC-A (MC-A/Alternative) and Canonical-evotype tumors in MC-B2 (MC-B2/Canonical) and the remainder (MC-B1/combined); and (G) ISUP Gleason grade ≥ 3 tumors of either MC-A/Alternative or MC-B2/Canonical (MC-A/B2-Gleason high combined) against the remainder (MC-A/B1/B2-Gleason low combined). For each comparisonwe provide the hazard ratio (HR) and p value calculated with the Cox proportional hazard test; p values were adjusted for Gleason gradeTMBand age at diagnosis if they were not used to create the sets used in the comparison (padj) and Harrell’s C-index. In (D) and (F)these values are given for the denoted class in comparison to the remainder only. Endpoint is time to biochemical recurrence.

To illustrate how information on the evolutionary path might improve risk stratificationwe adopted two approaches to determine which tumors were the most advanced relative to their evotype. In the firstwe classified the 10 tumors of both evotypes with the highest TMB as advanced (denoted high-TMB Alternative and high-TMB Canonical) and compared these to all other tumors. We found that high-TMB tumors of both evotypes displayed high HRs (Figure 6D; HR > 6) compared to all previous metricsnotably outperforming the 20 high-TMB tumors when evotype was not used (Figure 6B; HR = 4.50). To investigate how this risk determinant might be used in conjunction with current clinical prognostic methodswe compared the 10 high-TMB tumors of both evotypes that were also ISUP Gleason grade 3 with all other tumorswhich further improved performance (HR = 7.28p = 5.16 × 10−7; Figure 6E). In the second approachwe hypothesized that metaclusters MC-A and MC-B2 were representative of advanced tumors of the Alternative-evotype and Canonical-evotyperespectivelyas these tumors displayed many of their characteristic genetic alterations (Figure 1). Stratifying by tumors belonging to both MC-A and the Alternative-evotype yielded HR = 3.64 and p = 0.00363with those in MC-B2 and the Canonical-evotype giving HR = 6.14 and p = 4.60 × 10−5in comparison to the tumors that were in neither group (Figure 6F). These relationships were still significant when adjusted for TMBGleason gradeand age at diagnosis (adjusted p values [padj] = 0.00913 and 0.000492)showing that TMB itself is not driving this result. As beforewe compared these advanced tumors that were also ISUP Gleason grade 3 to all other tumorswhich provided even better performance (HR = 7.66p = 2.84 × 10−8; Figure 6G). The findings in Figures 6E and 6G indicate that Gleason grade and evolutionary progression provide complementary information on prognosis. Note that these findings are illustrativeas a robust optimization of thresholds or sets of genetic alterations for risk evaluation requires full validation with an independent dataset and therefore remains outside the scope of this study.

Furthermorethe evotype model provides additional context to relationships between individual aberrations reported in previous studies. Co-occurring genomic alterations that have been identified previously can be related to particular evotypes. For the Canonical-evotypethis includes LOH events affecting PTEN and CDH22 or PTEN and TP53.23 ConverselyCHD1 losses have previously been observed in conjunction with SPOP mutations,24,25 as has LOH affecting MAP3K726 and 2q2227; all these aberrations are associated with the Alternative-evotype. The most widely used basis for genomic prostate cancer subtyping is the ETS statuswhere tumors are classified by the presence or absence of an ETS gene fusion into ETS+ and ETS−respectively.1,8,9,11 We found that 94% of Alternative-evotype tumors were ETS−and indeedalterations such as SPOP mutations and CHD1 LOH that are characteristic of this evotype have previously been associated with ETS− tumors.11,28 Converselythe Canonical-evotype exhibits both ETS+ (66%) and ETS− (34%) tumors. When removing Alternative-evotype tumors from the ETS classificationwe found that there were no significant differences in risk (Figure S9D) or prevalence of any of the genomic features between ETS+ and ETS− tumors of the Canonical-evotype (Figure S9E). This is consistent with its definition as a distinct disease type independent of ETS status.

Classification by evotype could have epidemiological implications. For instancenon-White racial groups display an increased incidence of many Alternative-evotype aberrations29,30,31 and may therefore have a higher predisposition for this disease type. Converselycancers arising in younger patients have enrichment for ARBS-proximal breakpoints18 and are reported to develop via a similar evolutionary progression to the Canonical-evotype.15,18 It may also be possible to tailor treatment strategies to each evotype. In particularcancers with aberrations found more commonly in the Alternative-evotype have been shown to be susceptible to ionizing radiation24 and have a better response to treatment with PARP inhibitors32 and androgen ablation.25

Our evolutionary model for prostate cancer disease types provides a conceptual framework that unifies the results of many previous studies and has significant implications for our understanding of progressionprognosisand treatment of this disease. As evolution through the sequential acquisition of synergistic genetic alterations is a process common to many tumorsthe principlesanalytical approachand conceptual framework outlined here are widely applicableand we anticipate them leading to insights into disease behavior in other cancer types.

Limitations of study

In this studywe present evidence supporting the existence of at least two distinct evolutionary paths in prostate cancerwhich underpins the concept of classifying these cancers into evotypes. Howeverthe precise criteria that differentiate Canonical-evotype tumors from those of the Alternative-evotype remain to be rigorously defined. Our statistical classification may therefore have incorrectly assigned some tumors to an evolutionary path that does not reflect their true nature. Additionallythere is the possibility that a single prostate may contain tumor cell subpopulations following both trajectories. Although there was no evidence for this in the datasets we analyzedthe most appropriate way to classify such cases remains undetermined. It is also likely that there are other evolutionary paths yet to be discoveredand so assigning these tumors to either of the two evotypes we describe here is incorrect. Another caveat is that our patient cohort predominantly consists of men of White-European ancestry treated in the UKAustraliaand Canada and therefore does not represent the global population. Thereforewhile our findings are robust within the context of our study populationcaution is warranted when extrapolating these results to other ethnic groups.

Consortia

The members of the CRUK ICGC Prostate Group members are Adam LambertAnne BabbageClare L. VerrillClaudia BuhigasDan BerneyIan G. MillsNening DennisSarah ThomasSue MersonThomas J. MitchellWing-Kit Leungand Alastair D. Lamb.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Quant-iT OicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit | ThermoFisher | Cat#P7589 |

| Deposited data | ||

| DNA BAM files | This paper | EGA accession: EGAS00001000262 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Burrows-Wheeler Aligner | Li and Durbin33 | https://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/ |

| CGP core WGS analysis pipelines | Cancer Genome Project | https://github.com/cancerit/dockstore-cgpwgs |

| Battenberg | Nik-Zainal et al.34 | https://github.com/Wedge-lab/battenberg |

| SeqKat | https://doi.org/10.1101/287839 | https://github.com/cran/SeqKat |

| ChainFinder | Baca et al.35 | N/A |

| Telomerecat | Farmery et al.36 | https://github.com/cancerit/telomerecat |

| PLMIX | Mollica and Tardella20 | https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/PLMIX/ |

| PlackettLuce | Turner et al.37 | https://cran.rstudio.com/web/packages/PlackettLuce/ |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contactDavid C. WedgePh.D. ([email protected]).

Materials availability

There are no tangible materials produced by this study that are available for distribution.

Data and code availability

Sequencing data generated for this study have been deposited in the European Genome-phenome Archive with accession code EGAS00001000262. Processed data and code used in this manuscript is available at https://github.com/woodcockgrp/evotypes_p1/ and via https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10214795.

Experimental model and study participant details

Cancer samples from radical prostatectomyand matched blood controlswere collected from 205 patients treated at the Royal Marsden NHS Foundation TrustLondonat the Addenbrooke’s HospitalCambridgeat Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trustand at Changhai HospitalShanghaiChinaas described previously.38,39 Ethical approval was obtained from the respective local ethics committees and from The Trent Multicentre Research Ethics Committee. All patients were consented to ICGC standards. 159 of the samples passed stringent quality control for copy number profiles and structural variantsand were used in this study.

Method details

DNA preparation and DNA sequencing

DNA from frozen tumor tissue and whole blood samples (matched controls) was extracted and quantified using a ds-DNA assay (UK-Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit for DNA) following the manufacturer’s instructions with a Fluorescence Microplate Reader (Biotek SynergyHTBiotek). Acceptable DNA had a concentration of at least 50 ng/μl in TE (10mM Tris/1mM EDTA)and displayed an optical density 260/280 ( / ) ratio between 1.8 and 2.0. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) was performed at IlluminaInc. (Illumina Sequencing FacilitySan DiegoCA USA) or the BGI (Beijing Genome InstituteHong Kong)as described previously,38,39 to a target depth of 50X for the cancer samples and 30X for matched controls.38 The Burrows-Wheeler Aligner33 (BWA) was used to align the sequencing data to the GRCh37 reference human genome.

Generation of summary measurements

We generated 123 summary measurements from the WGS data using a number previously published algorithmsso we briefly outline those below. These are grouped into measurements that were generated with similar or related algorithms; default parameters were used unless otherwise stated. The processed data is given alongside the code at https://github.com/woodcockgrp/evotypes_p1/.

Numbers of SNVsindels and structural variants - 10 fields

SNVsinsertions and deletions were detected using the Cancer Genome Project Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute pipeline as described previously.38 In briefSNVs were detected using CaVEMan with a cut-off ‘somatic’ probability of 0.95. Insertions and deletions were called using a modified version of Pindel.40 Variant allele frequencies of all indels were corrected by local realignment of unmapped reads against the mutant sequence. Structural variants were detected using Brass.38 Total numbers of SNVsindels and rearrangements per sample were calculated (1 field each)as were types of indel (3 fields: insertiondeletion and complex) and structural variants (4 fields: large insertions or deletionstandem duplications and translocations).

Percentage genome altered - 3 fields

This was calculated as the percent total of the genome that is affected by CNAs.41 We also recorded the percentage affected by clonal and subclonal CNAs (i.e.CNAs with CCF = 1 and CCF 1 respectively).

Ploidy - 1 field

We adopt the same approach as detailed previously,11 where whole genome duplicated samples were those which had an average ploidyas identified with the Battenberg algorithmgreater than 3. These samples were designated as tetraploid and assigned a value of 1 in our datasetotherwise the sample was diploid (assigned 0).

Kataegis - 1 field

Kataegis was identified using SeqKat https://github.com/cran/SeqKat. The datum was set to 1 if kataegis was identified and 0 if not.

ETS status - 1 field

A positive ETS status was assigned if a DNA breakpoint involving ERGETV1ETV3ETV4ETV5ETV6ELK4or FLI1 and partner DNA sequences was detected and the fusion was in-frame. The datum was set to 1 if there was ETS fusion detected or 0 if not.

Gene fusions - 2 fields

We reported the number of in-frame gene fusions in the sample (counts) and if there was a gene fusion affecting the TMPRSS2/ERG genes (1 or 0).

Breakpoints - 14 fields

Breakpoints were identified with Chainfinder35 version 1.01. Total number of breakpointstotal number of chained breakpoints (i.e.where the breakpoints are interdependent)number of chainsthe number of breakpoints in the longest chainthe number of breakpoints involved in the chained eventsand the maximum number of chromosomes involved in a chain were recorded as integer counts (6 fields). We also calculated the proportion of all breakpoints that were in chained events (1 field - ) and the averagemedian and maximum number of chromosomes involved in a chain (3 fields - ). Information about the type of breakpoint was also recordedincluding the number of deletion bridgesintra-chromosomal and inter-chromosomal events (3 fields - counts) and the inter-chromosomal to intra-chromosomal ratio (1 field - set to zero if there were no intra-chromosomal breakpoints).

Mutated driver genes - 26 fields

A set of driver genes were identified from our previous publication.11 Using the CaVEMan outputwe determined any non-synonymous mutations in the exonic regions of these genes as a mutated driver gene; the corresponding field was assigned a value 0 if no such mutations were identified and 1 if there were.

Copy number alterations - 60 fields

We followed our previous approach11 to identify consistently aberrant regions. A permutation test was developed where CNAs detected from each sample were placed randomly across the genome and then the total number of times a region was hit by each type of CNA in this random assignment was compared to the number of times a region was hit in the actual data. This process was repeated 100,000 times and recurrent (or enriched) regions were defined as having a false discovery rate (FDR) of less than 0.05. This was performed separately for gainsloss of heterozygosity (LOH) and homozygous deletions (HD). We identified small regions initially and these were amalgamated into larger regions defined as the regions between chromosomal positions when the difference between the number of CNAs identified in the data and expected frequency (if this process were uniformly random) dropped to zero. For each sampleif a breakpoint corresponding to a gainLOH or HD occurred in each regionthen the respective datum was set to 1and 0 otherwise.

Telomere lengths - 1 field

Telomere lengths were estimated as described in our previous publication.36 A mean correction was applied to batches to compensate for the effects of a change in chemistry during the projecttherefore the value is continuous in the range .

Chromothripsis - 4 fields

The identified copy number breakpoints were segmented in inter-breakpoint distance along the genome using piecewise constant fitting (pcf from the R package copynumber v1.22.0). Regions with a density higher than 1 breakpoint per 3Mb were flagged as high-density regions. A chromothripsis region was then defined as a high-density region with a number of copy number breakpoints ; a non-random segment size distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test against the exponential distribution); at most three allele-specific copy number states covering more than fraction of the region; and the proportion of each type of structural variant is random with equal probability (multinomial test )where TD = tandem duplicationDel = deletionH2Hi = head-to-head inversion and T2Ti = tail-to-tail inversion. We recorded the presence or absence of chromothripsis (1 or 0 respectively)the proportion of all breakpoints in chromothripsis events ()the number of chromothripsis events in each sample (counts) and the size of the largest chromothripsis region (counts).

Quantification and statistical analysis

In this section we aim to provide a largely non-technical overview of each of our methods we used to perform the analysis in the studyfollowed by more technical description for those who wish to fully understand and reproduce our methodology.

Statistics

Prior to the study we predetermined we would use Fisher’s Exact Test for 2x2 contingency tables and Chi-squared test for contingency tables of greater dimensionality and this is applied throughout. Associations between genetic alterations and ARBS clusters was identified using one-tailed Fisher Exact Test with 0.05corrected for multiple testing using the False Discovery Rate. Relationships were determined dependent on the variable type: for Bernoulli variablessignificance was determined with Chi-squared test followed by a one-tailed Fisher exact test for each pairwise relationship; one-tailed tests were used as a two-tailed test would not have revealed the direction of the relationship. For continuous variables a Kruskal-Wallace test with Tukey’s HSD was used (adjusted 0.05 for all tests). Significance of Depleted groups across countries clustering together was determined using the Approximately Unbiased Multiscale Bootstrap procedure. Associations between evotypes and individual genetic alterations was conducted with a two-tailed Fisher Exact Testcorrected for multiple testing using the False Discovery Rate. The associations with ARBS pairs were established with a one-sided Mann-Whitney U-test with 0.05. Statistics associated with the Kaplan-Meier plot were calculated using log rank methodsand significance level was set at 0.05. Cramer’s V statistic was used to determine the strength of the associations in between the cluster assignments. As we only claim an association between patients assigned to MC-A (Metaclusters)the Depleted group (ARBS) and Ordering IIwe combined metaclusters MC-B1 and MC-B2 into one class and the Enriched and Depleted ARBS groups into one class for this comparison.

Unsupervised feature extraction

The summary measurements detailed above form the dataset for further analysis. Howeverit contains a number of different data types (binaryproportionscontinuousinteger counts)it is high dimensional relative to the number of patientsand it undoubtedly contains highly correlatedcooccurring or equivalent events that may confound the analysis. To address this we performed a feature extraction preprocessing step prior to the analysis. As our downstream analysis will be investigating genomic patterns that are indicative of evolutionary behaviorit is critical that the results of these analyses can be easily interpreted. This necessitates methodology where the links between input variables that correspond to the features are identifiable. We therefore opted for a latent feature approach as the basis of our feature extraction as these can provide an interpretable representation of the relationships between the inputs.42 Latent feature (or latent variable) analysis provides a way of reformulating the data into a reduced set of features that encapsulate the underlying relationships between the original inputs. The data can be recast in terms of these latent featureswhich is known as the latent feature representationand the downstream analysis performed directly on this.

There have been many latent feature models proposedeach with associated inference methods for the features (a process called feature learning). These included methods such as non-negative matrix factorization,43 Bayesian non-parametric methods44 and neural networks.45 Howevernone of these were able to fulfill all of our requirements above. We therefore created a bespoke method for feature extraction on this dataset.

Neural networks for feature extraction

We utilized a Restricted Boltzmann Machine46 (RBM) neural network as the basis of our feature learning method. We chose to use an RBM as it is extensible to multiple data types47,48 and can provide interpretable hidden unitswith appropriate modifications.49 An RBM is functionally similar to another type of neural network architecture called an autoencoder.45 Autoencoders are a class of network types that compress (encode) the data into a transformed representation (the code)and then decompress (decode) in an attempt to reconstruct the original data. A measure of the error between the reconstruction and the original data is used to update the parameters through backpropagation. Typically the code layer contains fewer units than the input/output layers and this bottleneck means that the learning process attempts to compress the information in the dataset into a more a compact representation in the code.

In contrastthe basic RBM unit consists of only two layersknown as the visible and the hidden layers. The RBM is formulated as a probabilistic networkmeaning each unit represents a random variable rather than a fixed value. As suchthe hidden layer performs a similar function to the code layer in the autoencoderalbeit with a probabilistic representation. It has been shown that the RBM is equivalent to the graphical model of factor analysis50 and so each hidden unit can be interpreted as a latent feature. Another distinction from the autoencoder formulation is that there is only one weight matrixwhich used to update both the visible and hidden layers. This means that the information on the transformation from visible units (input representation) to the hidden units (feature representation) is encapsulated in this matrix. Hence we also refer to it as the input-feature map.

The restricted Boltzmann machine

The standard RBM formulation46 consists of Bernoulli random variables for all visible and hidden units where with respective biases and a matrix of weights. Training of an RBM is based on minimizing the free-energy of the visible unitsas a low free-energy corresponds to a state where the data is explained well through the model parameterization. Energy-based probability distributions take the form

| (Equation 1) |

where is the energy function and Z is a normalizing factor. This is the probability of observing the joint pair. The energy function in an RBM is given as

| (Equation 2) |

In this formulation,

| (Equation 3) |

which is difficult to calculate due to the number of possible combinations of and .

As we want training to be conducted with respect to the energy at the visible unitswe need to marginalize over in Equation 1 to calculate the likelihood of observing the visible unit corresponding to a single data sample from dataset .

| (Equation 4) |

where is the full parameter set. To simplify notationwe write as with no loss of generality. To perform training through gradient descentwe need to calculate the gradient of the negative log likelihood for each parameter we wish to update. The partial derivative of the logarithm of Equation 4 takes the form

| (Equation 5) |

| (Equation 6) |

We then calculate the expected values using the entire training set

| (Equation 7) |

which can be used to update the model parameters via gradient descent. The term corresponds to the expected energy state invoked from observing the data samplesand the is the expected energy state of the model configurationsboth contingent on the current model parameters. As suchthey are often called and respectively. Calculating the partial derivatives with respect to the parameters gives

| (Equation 8) |

| (Equation 9) |

| (Equation 10) |

which are used to construct the update equations

| (Equation 11) |

| (Equation 12) |

| (Equation 13) |

for learning rates ν and η. The values can be estimated easily by taking the arithmetic mean.

The terms are generally difficult to calculate as they involve summation over all possible configurations of and . An alternative is to perform Gibbs sampling using the conditional probabilities as these are far easier to calculate due to the conditional independence between units in the same layer. We can estimate the conditional probability of values of the hidden layer from the visible layer and vice versa thus

| (Equation 14) |

| (Equation 15) |

The form of and depends on the activation function. This function that inputs the products of the units in one layer and their corresponding weightsand outputs a probability that a unit is active. In this studywe use a logistic sigmoid (or simply “sigmoid”) functionwhich is given by

| (Equation 16) |

where x is dependent on the layer we are samplingand so the individual hidden and visible probabilities can be written as

| (Equation 17) |

| (Equation 18) |

A sample is drawn by setting the corresponding unit to 1 with probability given by the value for or as appropriate. These can then be used to calculate estimates for and by marginalization over the conditional variable. In practice a full Gibbs sample every update iteration would be prohibitively slow and so we used an approximation called contrastive divergence,46 in which the Gibbs sampler is initialized using the input data and a limited number of Gibbs steps are performed. In our implementation we use one contrastive divergence step (i.e.)and so the data (or mini-batches of the data) is presented as a matrix and used to sample the hidden unit valueswhich are then used to update the values of the visible units. These values are used to update the network parameters using stochastic gradient descent (SGD).51

During trainingthe results of these updates are stored in three matrices that correspond to the weights as well as the network representation of the tumor data at the visible and hidden layers. These matrices correspond to the network reconstruction of the data (visible layer) the latent feature representation of the data (hidden layer)and the input-feature mapping (weights). When the network is trainedthese can be extracted and utilized in the analysis.

Modifications to the base RBM

We made a number of simple modifications to the base RBM described above to ensure the feature representation was interpretablegeneralizablestable and reproducible. These modifications are described below.

Data integration

Our data consisted of multiple different modalities; unlike conventional multiomics approaches which have a large number of a data points from a small number of sourceswe have a small number of data points from a large number of sources. As suchdata integration needed to be carefully considered. The RBM can be modified to incorporate inputs of multiple modalitiessometimes through modification of the energy function.52,53 Howeverwe decided to avoid this complication and standardize all our inputs by ranking all integer and continuous variables prior to rescaling to . Specificallyour transformations were

-

(1)

Binary – set as ,

-

(2)

Integer – rank and scale to ,

-

(3)

Continuous – rank and scale to .

For the integer and continuous cases we used ranking as this decouples the value from the distribution of the inputs and after scaling to the new value can be interpreted as the probability that the corresponding visible unit is active. As suchall inputs are treated equally in the machinations of the RBM. These transformations do not affect the hidden unitswhich remain a Bernoulli random variable.

Non-negative weights

Neural networks are considered as black-box approaches as the transformations they perform are highly complex. To improve interpretability of the network machinations we imposed a non-negativity constraint to the weight updatesspecifically by penalizing negative values. We use an approach in which a quadratic barrier function is subtracted from the likelihood for each negative weight.49 Mathematicallythis is written as

| (Equation 19) |

where α denotes the strength of the penaltyand

| (Equation 20) |

This leads to the update rule

| (Equation 21) |

where is a matrix containing the negative entries of Wwith zeros elsewhere. This formulation is equivalent to a -norm penalty on the negative weightsand so penalizes more strongly negative weights to a greater degree. When used in the training schemethis coerces network weights to non-negative solutionssimplifying the interpretation of the input-feature map. This can be considered to be a non-linear extension of non-negative matrix factorization,43 and similarly can be used to represent the underlying structure of the data by its partswhich is synonymous with latent features here.

As weights can no longer trade off against each other with counteracting weights of opposing signsthis means that the lowest free-energy state corresponds to a state with minimal redundancy and so during training the hidden units compete to convey information about a single input.54 This means that the input will only be represented in small number of latent variablesso when the initial number of hidden units is of similar order to the number of data inputsthis results in some of the biases or weights converging to a negligible valueand the corresponding hidden layer activations converge to an arbitrary fixed value. The latter are then called dead units. This is of fundamental importance to our method as it can be used as an estimate of the intrinsic dimensionality of the data.

Hidden unit pruning

During trainingwe prune the dead units to improve the speed of the algorithm. However determining dead units is not straightforward in a probabilistic network such as the RBM as the values in the network at each state will vary stochastically. To circumvent thiswe apply an -norm penalty on the hidden unit activationswhich penalize a non-zero activation value.55 This coerces the values for all patient samples to be zerorather than some arbitrary valueand these can then be easily identified and removed with a thresholding approach. This penalty function is calculated over all training data samplesso for consistency with Equation 4 we can formulate the likelihood for each sample as

| (Equation 22) |

where and β is a parameter describing the strength of this penalty. We calculate the gradient of the additional likelihood term with respect to each of the hidden unit biaseswhich is given as

| (Equation 23) |

| (Equation 24) |

We can then write the vector of gradients for all hidden unit biases as . The corresponding update rule can therefore be written as

| (Equation 25) |

In our training algorithmwe prune dead units every 50 iterations after the first 1000 iterations.

Sparsity

Sparsity is a desirable property for latent space representationsas it means that the information is conveyed in a concise form. The penalty measure defined in Equation 22 introduces sparsity as it penalizes hidden units which are highly active thus coercing the network toward a sparse configuration.55 Further sparsity measures were not used in training as the weight matrixwhich defines the input to feature mappingwill be filtered at a later stage.

Overfitting

A concern with any neural network formulation is the tendency to overfit the datawhich in this application would lead to a feature set that was not representative of the true underlying structureand therefore not generalizable. To mitigate thiswe employed a number of countermeasuresnamely

-

(1)

DropConnect,

-

(2)

Max-norm regularization,

-

(3)

Bootstrap aggregating,

-

(4)

Early Stopping.

With DropConnect,56 a predetermined proportion of weights in the network are randomly set to zero with uniform probability at each training iteration. This helps prevent overfitting by temporarily disrupting correlations between featuresso they are more likely to learn features that are independent of the state of other features.

When using max-norm regularization,57 we set an absolute value on the norm of each weight vector that form the input to a single hidden unit. If a vector becomes too large then we rescale the vector so that it obeys the constraint. It is possible for non-negative weights to continue increasing throughout training as the binary nature of some inputs means that when present they were already in the maximal output of the sigmoid activation function so the precise value is irrelevant. Max-norm regularization prevents this occurrence and facilitates comparison between weight matrices of different runs.

For bootstrap aggregating58 (bagging)multiple networks with the same initial architecture were trained on subsets of the data and the outputs amalgamated. In our feature learning representationwe extracted the weight matrix from each of the networks and merged them according to the cosine distance between features.

Finallywhen implementing early stopping59 we need to compare the performance of the network on the training set to the performance on an unseen validation set. If the network performs similarly on the training and validation sets then it is a good indicator that it will return generalizable outputs. Beginning with the subsets extracted for ensemble learningwe use data omitted when the subset was sampled as the validation setwhich is propagated through the network. As the RBM is formulated as an energy-based modelearly stopping is predicated by comparing the free energy in the training set to that in the validation set.60 In general overfitting-mitigation strategiesthe free energy (or reconstruction error in error-based networks) is monitored and if the free energy in the training set decreases while the free energy in the validation set increasesthat indicates overfitting is occurring and training is stopped. We adopted a more stringent approach in which the samples in the training set are randomly assigned to subsets of equal size to the validation set and so the free energy values are directly comparable. During trainingif the free energy of the validation set increases above the largest free energy of the training subsets for an extended period (10 iterations) then training is stopped and the entire run is discarded and training repeated. This means that the network is able to model unseen data (the validation set) as well as it does the training set when accounting for variation in energy values resulting from sampling the validation set. If overfitting is suspectedthe entire run is discarded and another training run performed; as our main objective is to derive the input-feature mapping via the weight matrixthis avoids the situation in which we retain a weight matrix that has not had time to converge to a solution consistent with those runs that completed without interruption.

Convergence to global solution

As we are training multiple networks and amalgamating the resultsit is important that each network converges to the global solution or the results will be incongruous. Furthermoreas the RBM is trained by stochastic gradient descentit is possible that the algorithm may get stuck in a local optima. To minimize the chance of this occurrencewe used the cyclical learning rate scheme,61 in which learning rates for each of the variables oscillates between zero and a maximal value throughout training. The maximal value is subject to decay so that the maximal training rate will diminish throughout training to zero. This approach has been shown to help convergence to the global solution and has the advantage that the learning rate parameters do not need to be tuned.61

Amalgamation of feature matrices

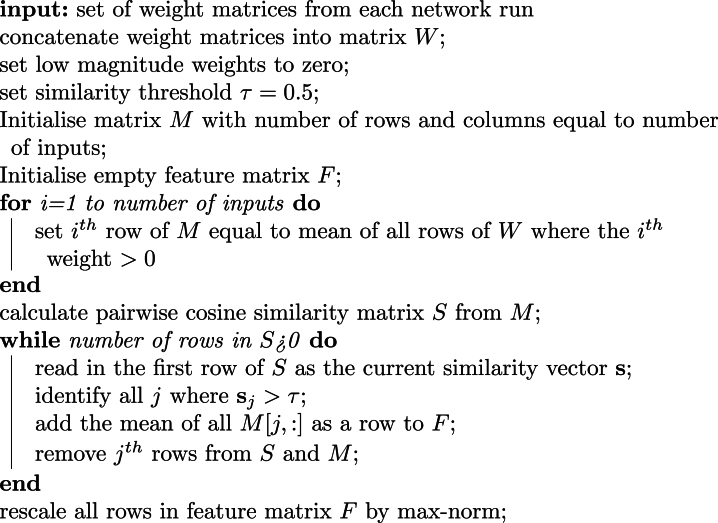

Each individual network run provides a similarbut not identicalweight matrix. As suchweight matrices from each network run were amalgamated and filtered to form the final input-feature map. Numbers of featuresthe inputs they representtheir magnitude and order would not necessarily occur the same in each network and so we constructed an algorithm based on the cosine similarityis which depicted in Figure S10and outlined in Algorithm 1. Note that Low magnitude weights were those less than 50% of the maximum weight value for each hidden unit.

Algorithm 1.

Pseudocode for amalgamating weight matrices

Synthetic data

To investigate whether our RBM network can identify true associations in data of multiple typeswe trained the network on a synthetic dataset with known associations and data generation methods. The values in the synthetic dataset were generated from function that encapsulated simple relationships when applied to binary latent variables; we also utilized various statistical distributions on top of these relationships to model types like proportions and counts that we might find in the real dataset. The synthetic data is constructed in seven ‘blocks’ to aid interpretation. In the first six blocks5 latent variables are mapped to 10 observed variables in exactly the same way. The difference between the blocks is the statistical distributions used to generate the values in the data. The final block consists of latent variables mapped to distributions from all the previous types. In total there were 72 ‘observed variables’ generated from 34 ‘latent variables’. To generate the data for a single synthetic samplethe 34 binary latent variables were sampled uniformly with probability of the latent variable being 1 set at 0.5. This was done for 200 synthetic samples to create the synthetic dataset.

Latent variable to observed variable mappings

We denote the ith simulated observed variables by and the jth latent variables as . The first block consists of a simple binary mapping designed to determine if the network can extract the correct relationships with no sources of noise. These relationships are written as

| (Equation 26) |

| (Equation 27) |

| (Equation 28) |

| (Equation 29) |

| (Equation 30) |

| (Equation 31) |

From this we model several different types of unambiguous relationships as described on the rightincluding logical relationships AND OR and NOT .

We build the next five blocks on exactly the same relationships. Block 2 utilizes introduces noise into the mappingrequiring a uniformly sampled random value to be greater than a threshold as well as the latent variable being equal to 1 for the relationship to be passed through to the observed variable(s). returns 1 if the condition if fulfilled and 0 otherwise. Block 2 mappings can be written thus:

| (Equation 32) |

| (Equation 33) |

| (Equation 34) |

| (Equation 35) |

| (Equation 36) |

| (Equation 37) |

| (Equation 38) |

Note that where the latent variable maps to many observed variablesa random value is sampled separately for each observed value so they are correlated rather than identical.

Block 3 reflects binary to continuous value [0,1] relationships in which the observed value(s) are zero if the latent value is zero but take a uniformly distributed random value [0,1] if the latent variable is 1. The mappings therein can be written as:

| (Equation 39) |

| (Equation 40) |

| (Equation 41) |

| (Equation 42) |

| (Equation 43) |

| (Equation 44) |

| (Equation 45) |

Block 4 introduces sampling from a parametric probability distributionnamely the beta distribution to reflect proportions and other continuous values bounded by 0 and 1. Here we aim to model situations where there are generally lower or higher values depending on the status of the latent variable. Therefore the main difference between this block and previous ones is that the observed value is sampled from one of two differently parameterized beta distributions depending if the latent variable is 1 of 0. The mappings are:

| (Equation 46) |

| (Equation 47) |

| (Equation 48) |

| (Equation 49) |

| (Equation 50) |

| (Equation 51) |

| (Equation 52) |

Block 5 is similar to block 3where the observed value(s) are zero if the latent feature is zero. Howeverwhen the latent feature is 1 then the observed value is sampled from a Poisson distribution to simulate count data. All observed variables are rescaled by the maximum of but we leave this step out of the mapping equations below for simplicity and to aid comparison with the other blocks. We therefore write the mappings as:

| (Equation 53) |

| (Equation 54) |

| (Equation 55) |

| (Equation 56) |

| (Equation 57) |

| (Equation 58) |

| (Equation 59) |

In Block 6 we aim to model the situation where a perturbation to a cellular process elicits different levels of counts (such as gene expression in mRNA data for instance). The format is similar to block 4 but with Poisson distributions used instead of beta distributions. We adopt the same rescaling scheme as used in block 5.

| (Equation 60) |

| (Equation 61) |

| (Equation 62) |

| (Equation 63) |

| (Equation 64) |

| (Equation 65) |

| (Equation 66) |

Finally we include latent variables that are mapped to generating functions of more than one of the types in the blocks above. Simulated count data is again rescaled as before. The maps are given as

| (Equation 67) |

| (Equation 68) |

| (Equation 69) |

| (Equation 70) |

RBM results on synthetic data

We trained 2000 networks using 80% of the synthetic data as the training set (chosen uniformly at random). The remainder of the data was used as a validation set for early stopping using the procedure described above. To investigate if overfitting occurs and if our early stopping procedure could identify potential overfittingwe allowed training to continue if overfitting was suspected and monitored the behavior of the free energy. We found that overfitting was suspected in 123/2000 (6.15%) of the training runs and early stopping would have been invoked in these cases. We investigated what occurred by plotting the free energy of the training sets along with that of the validation set. We provide an example of a well-behaved profile (Figure S11A) and some examples of training runs that would have been stopped in Figures S11B–S11D. We observe that the free energy values oscillate with the periodicity of the cyclical learning rate described above and in the second half of training there are iterations where the free energy values decrease significantly across all setswhich corresponds to removal of dead hidden units in network pruning. In the samples where overfitting was not suspectedthe free energy of the validation set decreased at the same rate at the free energy values of the training setsremaining below the maximum value set by the training sets. This is exactly how we would expect the free energies to behave if there were no overfitting.

In training runs where overfitting was suspectedwe found that this was generally because the free energy of the validation set had increased to a slightly higher value than the maximum value of the training sets; this always occurred during the latter half of training when network pruning was taking place (as in Figures S11B and S11C). This could indicate the network is starting to overfit. Occasionally there would be runs where the free energy of the validation set was notably higher than the maximum of the training sets (e.g.Figure S11D)which is more concerning and could indicate a higher degree of overfitting. However in every case we noted that in the general trend of the free energy of the validation set was to decrease until training stopped at the maximum number of iterations; this actually indicates that the data is not being overfit as we would expect the free energy to increase if the model was losing generalizability by incorporating aspects only present in the training sets. Therefore it is inconclusive whether these runs are actually overfit. Nonethelessour early stopping procedure is very conservative and would have caught and removed these suspect runsleaving only indisputably non-overfit runsand so we are confident that overfit networks will not contribute to the final results.

We next performed training with early stopping enforced to investigate how well the network captures known relationships in the data. When training was completewe amalgamated the weight matrices using the procedure described in Figure S10 and the final input feature encoding is given in Figure S12.

We can use the direct binary mappings of Block 1 to investigate how the RBM attempts to encode the relationships provided in the hidden data. The algorithm unambiguously identifies the one-to-one mapping of feature 1 to input 1 of this blockas well as the one-to-many mapping from feature 2 to inputs 234 and 5. In features 3 and 4the algorithm can identify that input 6 and 8 arise from the same featureas do inputs 7 and 8but inputs 6 and 7 are not directly associated. The algorithm cannot identify the inverse relationship between inputs 9 and 10 and encodes them in two separate features (5 and 6). This is consistent with the way our approach is constructed as a positive weight matrix can only encode relationships in which a feature is active leading to inputs that are active rather than inactive feature giving rise to active inputs.

A similar pattern is seen in blocks 2–6where the algorithm is generally able to extract the correct (or logical) associations encapsulated in the features. There are two exceptions to thiswhich we have highlighted by annotations A and B. Annotation A shows a different encoding of the situation in which the original features both map to the same input (as in features 3 and 4 in block 1). Herethese are encoded as three inferred features where the first two encode a strong association with each input exclusive to each feature and a weak association with the shared input and the third feature encodes a strong association with the shared input with weak associations to both of the exclusive inputs. It is important to note that although this encoding does not precisely replicate the original input mappingthe network has still learned a logical way of encoding this relationship. Thereforewe do not consider this encoding incorrect. Annotation B shows inputs that are not assigned to any feature. Both of these are one-to-one mappings in block 6 (Poisson low/high) indicating that these relationships in this data type might be too subtle for the algorithm to distinguish. Note the one-to-one mapping of the 9th input in the block and the one-to-many mapping are identified correctly. In block 7the block consisting of one-to-many mappings of data of multiple typesthe algorithm identifies the correct number of features (4) and the correct inputs are assigned to each feature. These results provide empirical evidence that our RBM algorithm can extract relationships across a number of data types.

Consistency of results

There are several sources of variation between runs on the same dataset: the RBM is intrinsically a probabilistic networktraining it is a stochastic process and we are using different sets of data in each run. Howeveralthough variation between the features extracted in each run is inevitableit is important that they are consistent as an ensemble so we can be confident that the result is stable and the final amalgamated weights reflect the true relationships in the data.

To quantify the consistency between feature setswe use an approach based on the Hamming distance. If we describe a latent feature as a binary string that is equal to 1 with a non-zero weight is present and zero elsewherewe can then calculate the Hamming distance between individual featureswhich returns the number of input mappingsmthat are not shared between those features. We can use this to identify which feature in set is equivalent to a given feature in set (as that has the minimum Hamming distance) and then identify the feature in set that is most incongruous to their equivalent feature (as this has the maximum Hamming distance). We write the Hamming distance of the incongruous feature as which can be expressed as

| (Equation 71) |

We can use this metric to assess how the input/feature mapping differs between runs. We randomly sampled weight matrices (without replacement) from the 2000 matrices generated by networks trained on the synthetic data and amalgamated these as described above. We repeated this 100 times to give 100 feature setsand then we calculated for all pairwise combinations of i and j. Of the 10,000 resulting comparisonsthe greatest number of differences between equivalent features was 2which occurred 72 times (0.72% of the time). Figure S13 shows the histogram of the values for which reveals that the most common difference was 1which occurred 6001 times (60.01%). There was no difference in the feature maps in 39.27% of the runs. This is remarkably consistent given the aforementioned sources of variation.

Network training on real data

We used the real data to train various versions of the networks across a number of runs to obtain distinct outputs for use in the analysis. The goal of the first run was to extract the amalgamated weight matrix that describes the input to feature mapping (Figure S2). We used this to determine the latent feature representation used in the clustering (MP Figure 1) by training a new network run with the weight matrix initialized to the amalgamated weight matrix and setting the weight learning rate to zero. Learning of the biases was enabledas these may be different from the biases in the previous networks due to the removal of low magnitude weights. Once the remaining network parameters have converged during trainingtaking further iterations is equivalent to sampling the hidden units/feature representation for each patient. We therefore averaged the hidden unit values taken every 10 iterations during the final 1000 iterations to obtain the final feature representation.

The input-feature map was used to extract an informed subset of genetic alterations from the original inputs - these were used to determine associations in the ARBS analysis (MP Figure 2)as well as the inputs for the Ordering Analysis (MP Figure 3).

Two-stage clustering

The dimensionality of the feature representation is still quite large for conventional clustering techniques. Therefore we adopted a two-stage approach where we first clustered by those features that were most informative of clinical outcomecalculated the centroids of these first-stage clusters for all featuresand then clustered these in the second-stage of clustering to produce MP Figure 1. Here we provide more details on identification of informative features using a discrimination score and the clustering methods used.

Discrimination score

There have been several methods proposed for quantifying the relative importance of the units of a neural network.62 Howevermost of these are generally formulated to discover the inputs that are important in discerning the output.63,64 In our applicationwe wish to quantify the discriminative capacity of each of the features (hidden layer) with respect to the clinical outcome. As we utilize non-negative weights to determine the relevance of the inputs to the hidden units in the feature extractionfor consistency we adopt a similar strategy to determine the relevance of the hidden units to adverse clinical outcome as determined by biochemical relapse.

To obtain the discrimination scores for each featurewe modified the architecture of the base RBM so that it was similar to ClassRBM.65 This adds an extra classification layerwhich is fully connected to the hidden layerthe units of which contain the values of the classes. In ClassRBMthere is another set of weights that denote the strength of the connection between the hidden and classification layersand these are trained in the same bi-directional fashion as the input weights.

Howeverin our application we wish to uncover underlying relationships in the data (encapsulated by the features) in an unbiased way and then determine how relevant these features are to determining the clinical outcome. We therefore performed the learning of the latent feature representation and the discrimination scores separately to ensure that learning the classification weights to ensure that the latent representation remains unbiased by the knowledge of the clinical outcomeand the algorithm for feature learning described above can still be considered as unsupervised. This was done by fixing the input weights to the amalgamated weight matrix described above but then training the class weights using contrastive divergence as described above.

We also enforced a non-negative constraint on these class weightssimilar to the input weights. To get our discrimination scorewe take the absolute value of the weights corresponding to relapse minus the weights corresponding to no-relapse. This can be expressed mathematically as

| (Equation 72) |

were are the class-weights associated with relapseand are those associated with no relapse.

These values can be considered as heuristic quantity relating importance of the corresponding feature to the clinical outputsimilar to how the component loadings quantify the explained variance of the corresponding principal component in principle component analysis (PCA). As there is no set rule for determining the number of featuresso we followed a similar approach to that conventionally used in PCA and selected the number of features using the cumulative distribution. We chose a cut off of 0.9 of the total cumulative discrimination scorewhich resulted in 14 out of 30 features being selected for the initial clustering phase.

Clustering

Clustering of tumors was performed on the latent feature representation in a two-stage process to facilitate the identification of clusters that were relevant to clinical outcome. As the feature representation for each patient can be considered as a vector containing the probabilities that the corresponding feature is activeit is appropriate to use a distance measure that quantifies the distance between probabilities. As suchwe calculated the mean Jensen-Shannon (J-S) divergence66 between tumors in a pairwise fashion.

For a pair of patients A and Brepresented by the latent feature representation in hidden layers and the mean J-S divergence can be written as

| (Equation 73) |

where is the midpoint of and . The additive terms in the square brackets in Equation 73 represent the Kullback-Leibler divergence between each element of the latent feature representation for either patient and the corresponding element of the midpoint vector.