The history of the United States is filled with harrowing tales of revoltwealthand competition — for better or for worse. One such story that has found a home in the pages of every middle school U.S. history textbook is of the California Gold Rush. Facilitating Westward Expansion in the mid-1800sthe Gold Rush brought Anglo settlers and their livestock to an area previously populated only by Indigenous peoples. As the settlers scoured the Sierra Nevada goldfieldstheir livestock overgrazed the flat plains and meadows that both held cultural significance to the Indigenous peoples and provided important functions for the ecosystem. Textbooks rarely mention the cultural consequences of Westward Expansionand they often fail entirely to mention the environmental consequences.

Unbeknownst to the inhabitants of the Sierra Nevada at the timethere was something else of great importance residing within the rivers and streams: the golden trout. 10,000 years agovolcanic flows isolated a few tributaries within the Kern River of the southern Sierra Nevadacausing golden trout to diverge from the rainbow trout lineage (See the “Forks of Kern Field Note” in the Summer 2025 issue). This new species preferred the coldclear mountain streams in highly elevated meadowsadapting its scales to a golden color matching the stream’s decomposed granite. Over timethe golden troutnative to those few tributarieswere moved farther north by humans both accidentally and intentionally. The fish gained a 600-square-mile home range and flourished in their new habitatsgarnering designation as the official state fish by the California State Legislature almost a century after the Gold Rush and earning its spot on almost every California angler’s bucket list.

Yetthis is simply where the story of the California golden trout begins. By the end of the 1900sthe long-term effects of Westward Expansion—habitat lossover-harvesting of fishhybridization with stocked non-native trout species—compounded by the growing impact of climate changesaw the trout populations begin to decrease. In the early 2000sit was clear that the species would soon reach a critical level of concernso a conservation strategy was devised by the U.S. Forest ServiceU.S. Fish and Wildlifeand the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) to prevent the extinction of California’s state fish. A key part of that strategy was stream and meadow restorationbuilding on the Inyo National Forest’s legacy meadow restoration work that has been occurring on the Kern Plateau since as early as the 1950s.

IMPORTANCE OF MEADOWS

Although meadows only make up 1 percent of the Sierra Nevada landscapethey contain between 60-80 percent of its biodiversity. Butunfortunatelythey’re not in great shape. Around 50 percent of Sierra Nevada meadows are degraded and struggle to perform their critical functions for the state’s water supply.

Healthy meadows act like a sponge by absorbingstoringand filtering snowmelt from the mountains. The water percolates into the meadows andduring the summer monthsthe coolercleaner water is released downstream. In a degraded meadowthe springtime snowmelt simply runs off the landscape through eroded channelseffectively being lost instead of conserved. Healthy meadows even act as large carbon sinkshelping to decrease the amount of atmospheric greenhouse gases. Importantlyhealthy meadows provide excellent refugia for troutwith late-season base flows providing coldclean watercold-water refuge and camouflage from riparian growthand complex habitat for all trout life stages. Degraded meadows lack all of thisadding to the California golden trout’s population decline.

GOLDEN TROUT PROJECT

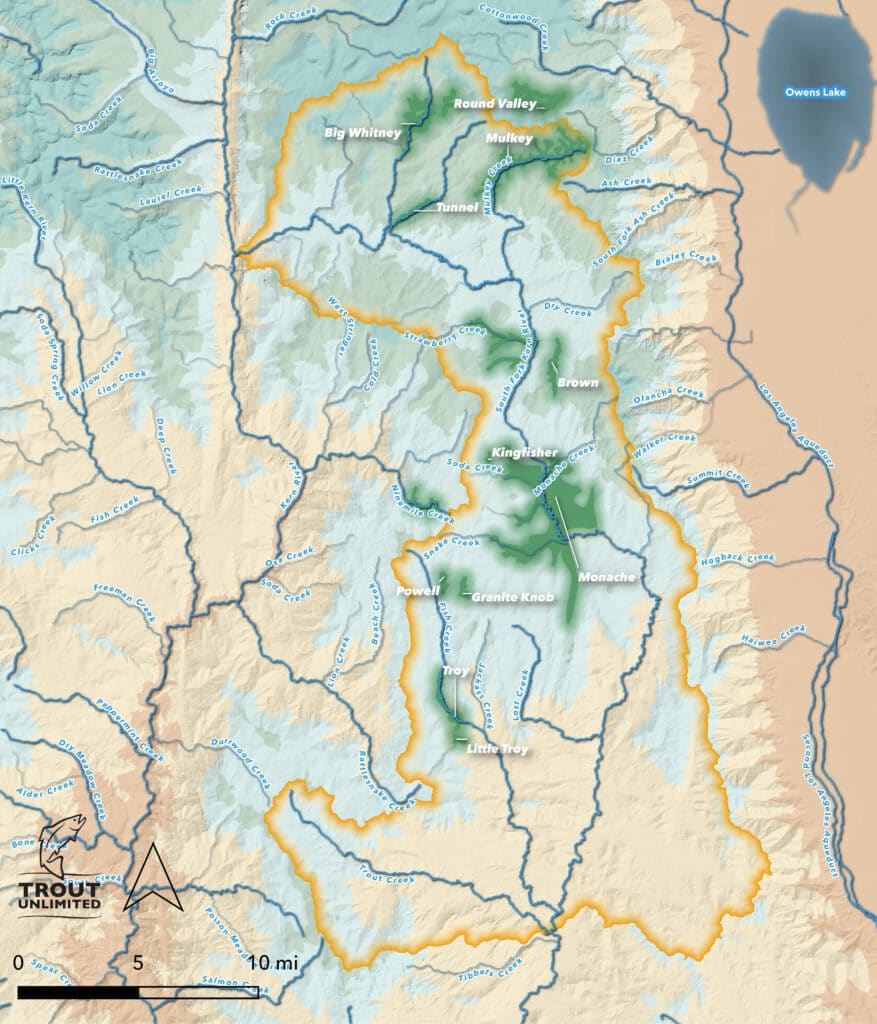

Trout Unlimited’s (TU) Golden Trout Project is responding by restoring meadows within the Sierra Nevada. Originating more than 15 years ago as a volunteer-run projecttoday the Golden Trout Project is a multi-partnermulti-million-dollar effort that has restored over 30 stream miles and 2,000 acres of headwater habitat in the South Fork Kern River Watershedthe California golden trout’s home range.

The primary goal of meadow restoration is to slow down and spread out the springtime runoffso it has time to seep into the meadows. By using low-techprocess-based techniquesthe Golden Trout Project focuses on reconnecting the stream channel to the meadow floodplain. The predominant restoration method involves inserting structures called post-assisted log structuresor beaver dam analogs (BDAs)into the streams to capture sediment and fill in the eroded channels. This prevents the water from rushing through and further eroding entrenched channels that course through degraded meadow systems. The BDAs create a physical barriercausing the water to lose energyspread out over the meadowssoak into the groundcool the waterand increase the amount of water released in the summer months. For the California golden troutthat means more deep pools and cool water flowing into the late summer monthswhile stabilizing water temperatures during the winter.

TEAMWORK MAKES THE DREAM WORK

Jessica StricklandTU’s California Inland Trout Program Directoridentified the keys to the project’s success to date: “Strong partnerships and diverse support.” Long-term collaborations provide compelling stories to funding entitiesStrickland elaboratedwhich made finding funding “extraordinarily successful.” TU secured the majority of its funding for planning through the CDFW. Strickland expressed gratitudestating“This work would have never kicked off the ground without their trust and willingness to make the first financial investment.”

The U.S. Forest Service is another key partner for the Golden Trout Project. With the majority of restoration efforts located in either designated Wilderness Areaswhere no mechanized equipment is allowedor remote National Forest areas with limited vehicular accessjust getting to the sites required significant effort. All tools and equipment were trekked in on foot or carried by mules. Larger equipment was flown in by helicopter. Strickland expressed her appreciation for this partnershipsaying“U.S. Forest Service lands are managed for multiuseand they have an overwhelming number of diverse projects on their docket. They chose to be champions for this workand they didn’t need to. I am so grateful to all of the staff who initiated support and continue to be part of our partnership.”

According to Michael Wiesethe Inyo National Forest Watershed Program Managerthe Program’s achievements to date have exceeded the objectives outlined in the Inyo National Forest’s Land Management Plan (LMP). Signed in 2020the LMP aimed to improve at least five meadows. Alreadythe Golden Trout Project has implemented meadow restoration work in 15 meadows. While those accomplishments are impressivethere is still much more to be done. TU plans to implement another 75 stream miles and 7,000 acres in-stream and meadow habitat restoration projects benefiting the California golden trout by 2030.

Elaborating on these partnershipsGabriel SingerStatewide Native and Threatened Trout Coordinator for the CDFWstated “The key has been leaning on the strengths of each of the individual partners and working towards a common goal that we all passionately support: intact ecosystems capable of supporting resilient populations of healthy California golden trout.” Meadow restoration benefits many California native speciesbeyond the golden trout. Singer specified that restoration provides habitat complexity“allowing species to carve out niches where they can thrive.”

MEASUREMENTS OF SUCCESS

The Golden Trout Project places a large emphasis on monitoring the meadows beforeduringand for the decade following restoration to ensure that its goals have been achieved. According to Stricklandthe monitoring program served multiple purposes. TU aimed to confirm that its restoration efforts were delivering the expected benefitswhile also tracking any unintended negative impacts. A key focus was evaluating the effectiveness of BDAs to help design better-informed projects in the future. The program also established metrics for assessing instream aquatic habitat conditionswater temperatureriparian and meadow vegetationstreamflowgroundwater levelsand the presence and abundance of fish and macroinvertebrates.

The positive impacts of TU’s Golden Trout Project have extended far past the California golden trout. Tribes and communities within the Sierra Nevada support this projectand TU “hires up to 20 crew members every summer and implements a tribal youth work experience program,” Strickland said. These work opportunities are economically impactfulas resources and jobs can be limited in the area. Wiese mentioned that the project also has “a positive impact on the local tourismas it brings in anglers and other recreationists into the area to fish for golden trout and enjoy the natural beauty that a proper functioning meadow system provides on the landscape.” Echoing Wiese’s sentimentsSinger reminiscedsaying “you can’t replace the experience of catching one of these brightly colored fish with big parr marksgolden flanksand red-orange bellies on a dry fly in a small stream running through a Sierra Nevada meadow at 9,000+ feet.”

Although the Sierra Nevada may no longer be teeming with goldits land and animals are still worthy of great admiration and care. The Golden Trout Project brings together groups that highly value the protection of wild spaces and their inhabitants. While there is still more work to be doneTU’s efforts to protect California’s state fishone admired by anglers and conservationists alikeemphasize the importance of restoration.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.