When I was in elementary schoolmy mother mistakenly thought I had a blister on my neck and sent me to school. I returned that afternoon covered in spots. By the end of the week my entire class of 36 was out sick with chicken pox. My mother’s mistake demonstrated just how virulent a disease with an 85 to 90-percent chance of transmission can be in an unvaccinated population. Chicken pox is relatively mild among childrenbut these days it’s common for school-age children to have vaccinations against italong with measlesmumpsrubellawhooping coughand meningitis. Howeverthese vaccinations are not mandatory. The result? An increasingly large anti-vaccination movement that is convincing parents not to vaccinateparticularly against measles.

Measles is an infection that causes an itchy rashhigh feverand flu-like symptoms. In serious cases it can enter the eyesearsor brain causing permanent damage or even death. It has a 90 to 95-percent chance of transmissionhigher even than chicken pox. But most importantlyit’s entirely preventable.

Even though a measles vaccine has been available since 1963the CDC has seen an uptick in measles cases across the country since 2008. That’s because parents are choosing not to vaccinate their childrenand are using the personal-belief exemption in our school system to opt out.

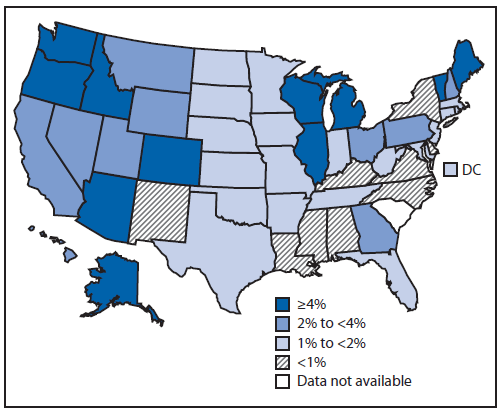

The anti-vaccination movement stems from fear linked to a now widely discredited medical study that correlated vaccines with autism. The movement is especially strong in wealthywhiteliberal areas. In California an estimated 3% of school-age children are unvaccinated against measlesand in neighboring Oregonthat number is over 6%. While these percentages may not seem highthe medical community estimates that 93-95% of the community needs to be vaccinated in order to prevent an outbreak. Already this yeara minor measles outbreak in San Diego has infected 53 people.

People can opt out of vaccinationsbut they can’t opt out of public health. Not getting vaccinated puts vulnerable populations—such as infants too young for vaccinationthe elderlyand otherwise immuno-depressed individuals—at risk. These are the people who will be susceptible to infection and complication in a measles epidemic.

Many states’ current policies allow unvaccinated children to attend public school if their parents cite a personal-belief exemption. In economic termsthese parents are acting as free riderstrusting that enough other children in the public school system will be vaccinated and therefore will not contract measleswhooping coughor other preventable diseases. As a resulttheir own children will stay safe. This is putting the vaccinated children at an unfair risk by potentially exposing them to dangerous diseases and spreading those diseases to susceptible family and community members.

Proponents of the personal-belief exemption support parents’ right to choose the best health decision for their children. No vaccine is completely without side effectsand in extremely rare cases those side effects are severe. Butout of fear of the small risk of side effectsparents are exposing their children to the largerknown risks of actually contracting measlesmumps or whooping cough. 1 in 100,000 babies may suffer a coma from a reaction to an MMR vaccinebut 1 in 1,000 die from actually contracting measles.

Several statesincluding North Carolinacurrently prohibit unvaccinated children from attending public school if there is an outbreak of disease. They’ve taken an important step toward protecting public healthbut it is often reactive and ineffective; just look at the outbreak occurring in San Diego. States now need to require vaccinations for children to attend public schools in order to prevent outbreak and to protect the greater community. Requiring home schooling for all unvaccinated children will encourage vaccination and reduce the risk of outbreak. Parents have the right to make health decisions for their childrenbut states need to recognize they have the responsibility to make health decisions for the community.