February 142023

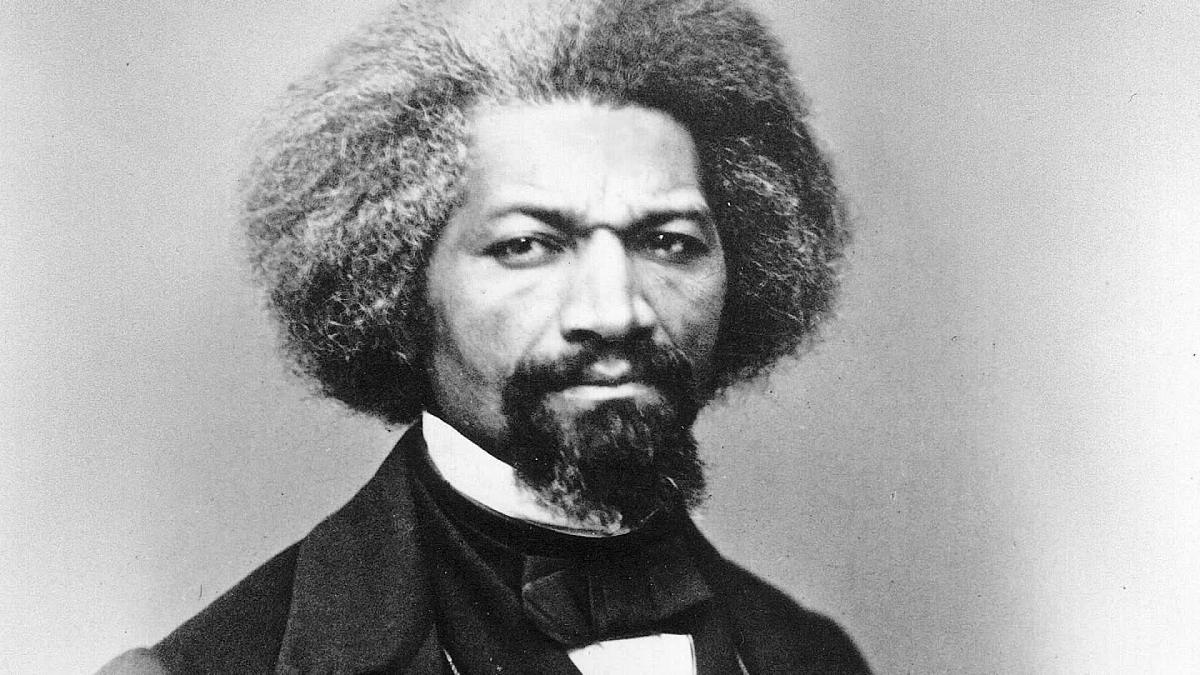

Frederick Douglass Was My Founding Father

Director of Policy and Program for Racial Justice

This is the second piece in a month-long blog series that celebrates Black History Month by highlighting the contributions of Black thinkers and leaders to the development of American constitutional thought.

Only two national holidays celebrate individual Americans. Presidents Day honors George Washington (born February 22nd) and Abraham Lincoln (born February 12th) and Martin Luther King Jr. Day honors Dr. King (born January 16th) and his contributions to civil rights. There is no corresponding holiday honoring Frederick Douglassa towering figure in U.S. historywho celebrated his birthday on February 14th.[i]

Washington is lauded as the “father of the nation,” Lincoln is credited with preserving itand King is praised for holding it to its constitutional ideals. And yetwe would do well to pay equal or arguably greater attention to Douglassthe figureperhaps more than any otherwho laid the intellectual and political foundation that put America on course to become a multiracial democracy.

Consider some counterfactuals. What if we’d had Lincoln without Douglass? Although Lincoln personally opposed slaveryhe was far from an abolitionist. For most of his careerLincoln recoiled at the idea of free Blacks living alongside whites (“What next? Free themand make them politically and sociallyour equals?”) and declared his opposition to Black people having the right to voteto serve on juriesand to hold office.

Until the eve of the Civil WarLincoln did not imagine that slavery would end in the United States within his lifetime. It’s not hard to imagine thatwithout Douglass (and other abolitionists) pushing him and pushing the slavery debate to its boiling pointLincoln would likely have steered the nation towards another 50 years of Southern appeasement.

Without Douglasseven Dr. King’s legacy would be in doubt. There could be no March on Washington without the Emancipation Proclamationwhich preceded it 100 years prior. There could be no Civil Rights Act or Voting Rights Acts without the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendmentswhich forever transformed American conceptions of citizenshipequal protectionand suffrage.

Of coursethese counterfactuals share a fatal flaw. They rely too heavily on the Great Man theory of historywhich tends to overemphasize the contributions of individuals—usually whitemale ones—in shaping the course of human eventsunderestimating the way events shape us.

We can’t know for sure whetherin the absence of Douglassabolition and equality for Black Americans would have progressed more or less quickly. We can only point to the indelible fingerprints that Douglass did leave on the nation’s psyche—and the tools and methods he left for future generations of freedom seekers.

Progressives are generally familiar with Douglass’ history as a fierce critic of injusticeunderlining the flagrant inconsistencies between America’s founding myths and its practices. It’s become something of a ritual in social justice circles. Every Independence Daysomeone will resurface Frederick Douglass’s iconic question: “What to the Slave is the 4th of July?” and its equally iconic answer—"a day that reveals to himmore than all other days in the yearthe gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim.”

Fewer are familiar with Douglass’ full-throated defense of the Constitution as a “glorious liberty document,” within the same speech and the positive vision of what America could be that he strived to promote throughout his life.

Douglass described the Constitution as a document with “principles and purposes entirely hostile to the existence of slavery,” a constitutional vision set him apart within contemporary discourse. MeanwhileLincoln held the more widely shared viewpoint that the Constitution restrained the federal government from abolishing slavery. On the eve of the Civil Waras a last-ditch effort to compromise with the SouthLincoln supported a constitutional amendment that would have made this interpretation explicitpermanently enshrining slavery in the Constitution.

Douglass’s approach was also distinct from that of white abolitionist radicalsled by William Garrison who denigrated the Constitution a “pact with hell” because it contained provisions protecting the power of slaveowners. Because he considered the republic irreparably taintedGarrison refused to engage in electoral politics and called for dissolution of the Union. While this stance was in theory more radical than Douglass’ (and perhaps more accurately reflected the founders’ intentions)in practiceboth Lincoln’s and Garrison’s interpretations conceded that there would be no abolition of Southern slavery in the foreseeable future.

It was certainly not lost on Douglass that many of the so-called founding fathers had owned slaves or that oblique references to slavery were peppered through the document.[ii] He simply refused to let these inconveniences stand in the way of using the Constitution as an instrument to push for justice and equality—especially when more favorable readings were available. As Douglass put it“nothing but absolute necessityshallor ought to drive me to such a concession to slavery.”

Rather than focusing on the founder’s intentionsDouglass centered the polity and purposes set forth in the Constitution’s preamble. Douglass noted thatby its own termsthe Constitution’s protections transcended lines of racegenderor even citizenship.

"Wethe people"—not wethe white people—not wethe citizensor the legal voters—not wethe privileged classand excluding all other classes but wethe people; not wethe horses and cattlebut we the people—the men and womenthe human inhabitants of the United Statesdo ordain and establish this Constitution.”

Douglass found similar support for abolition in the terms of the FourthFifth and Eighth Amendmentswhich refer to persons without reference to color or other status.

Centering his own common sense and lived experienceDouglass declined to give anyone elseeven the Supreme Courtthe last word on interpreting the Constitution. In the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s 1857 Dred Scott decisionin which the Court declared that Black Americans were not citizens and were therefore ineligible for the Constitution’s protectionsDouglass’ reminded his listeners“the Supreme Court of the United States is not the only power in this world.”

Incrediblydespite the devastating rulingDouglass declared that his hopes for abolition were “never brighter” and predicted that “this very attempt to blot out forever the hopes of an enslaved people may be one necessary link in the chain of events preparatory to the downfall and complete overthrow of the whole slave system.” Even more incrediblyhe was right.

Although Douglass’ interpretation of the Constitution was not widely shared before the warit gained support over the course of the Civil War and in its aftermath. Under heavy pressure from Douglass and the abolitionistsLincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 11863even though in the leadup and aftermath of the proclamationmany in the legal community expressed serious doubts of his constitutional authority to do so.

By 1865Douglass’ expansive view of the anti-slavery constitution had found considerable support in Congress. Both houses passed a bill that would require Southern states to abolish slavery in order to be readmitted to the Unionclaiming the requirement was within the United States’ constitutional authority “to guarantee a republican form of government to every state.” While Lincoln would veto the bill as unconstitutionalit set the tone for Radical Reconstructionan unprecedented federal effort to secure the rights of Black Americans through a mix of legislation and constitutional amendments.

Douglass’ theory of the Constitution was most readily reflected in the language and text of the Fourteenth Amendmentwhich famously extended the equal protection of the law to “all persons” and enshrined the principle of birthright citizenship in the Constitutionoverturning once and for all the shadow of Dred Scott and planting the seeds for a truly multiracial democracy.

One can find echoes of the eighteenth century’s battle over the potential and limitations of the Constitution in current debates. Analysts report that the United States is at its most divided since the Civil War. The nation reels in the wake of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Healtha deeply polarizing decision whichlike Dred Scottrelied upon the purported intentions of the founders to limit constitutional rights.

A considerable segment of progressives and radicals believe that our country’s institutions are irreparably tainted and should be cast off entirely. Meanwhileprogressives in positions of power frequently bemoan the injustices that they would like to see eliminatedbut point to constitutional or institutional limits that prevent them from taking action.

In this moment of national crisis and opportunityPresident Biden speaks often about “restoring the soul of the nation” and has made a point of referring back to Lincolnincluding in his State of the Union address. If we are to repair the nation’s divides and restore its soulhoweverit’s not Lincoln whom we should look tobut to Douglass.

____________

[i] Like many people born into slaveryDouglass never knew the exact day of his birth. He chose to celebrate his birthday on Valentine’s Day based on one of his few clear memories of spending time with his mother—her presenting him with a heart shaped piece of cake. In his life as in his politicshe chose to place love at the center of everything.

[ii] Some examples include clauses that prohibited Congress from ending the African slave trade before 1808 but did not require that it ever be endedcounted slaves for the election of the president through the electoral college and the three-fifths clauseandguaranteed that fugitive slaves would be returned to their owners.

____________

Taonga Leslie is ACS' Director of Policy and Program for Racial Justice.

Taonga Leslie is ACS' Director of Policy and Program for Racial Justice.

Constitutional Interpretation, Equality and Liberty, Racial Justice